Originally published in The American Scholar

On the evening of March 6, 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron and his wife, Brigitte, went to the theater. They saw a performance of Par le Bout du Nez, By the Tip of the Nose, about a French president who has an itch in his nose so serious that he is unable to speak.

Macron at the time had made no public statement about the encroaching pandemic, even though he was facing the imminent arrival of COVID-19 in France, not to mention the ravages the virus was already inflicting on Italy and Spain. His message in attending the play, according to the theater owner: Life goes on. Except for those with pre-existing conditions, there was no reason not to go out if standard hygiene practices were followed.

B et E Macron étaient hier au Th Antoine à Par le bout du Nez avec F Berléand et FX Demaison

Le Président a précisé que malgré le Coronavirus, la vie continuait & qu’il ne fallait pas (sauf pr les pop fragiles) modifier les habitudes de sortie, en suivant les règles d’hygiène— Jean-Marc Dumontet (@Jmdumontet) March 7, 2020

A few days later, the 43-year-old president declined to cancel the first round of municipal elections across the country, set for March 15, because “it was important for … our democratic life and the life of our institutions.”

I remember that Election Day. It marked the first time we saw widespread use of hand sanitizer, which was deployed at polling places. Parisians, and those elsewhere in France, turned out to vote. Then they flocked to parks, beaches, riversides and other locations to crowd together and enjoy one of the first sunny days of the year.

And one of the last they could spend outside. The very next evening, Macron appeared on national television to announce that the country would go into lockdown — the following day. People would have to stay in their residences except for certain allowed reasons. Only essential businesses, such as grocery stores, could remain open. Museums, gyms, libraries, shopping centers restaurants, cafes and theaters would have to shut their doors.

The streets of the city were filled with posters for events that now wouldn’t happen.

That was the end of Par le Bout du Nez, which won’t open again until this coming May at the earliest. Also canceled: The second round of municipal elections, planned for March 28. They were held three months later.

Practically everyone has a story about what their governments did when faced with the pandemic. The U.S. story is particularly unpleasant, as we all know. The French response, though, was unique in the world in certain ways, and Macron’s early actions reveal almost all of them: a reluctance to change course, a dependence on decisions from the top, a fixation on bureaucratic solutions and a refusal to apologize for mistakes. It accounts in part for both France’s successes and its failures against COVID-19.

Globally, France is in the middle of the pack in terms of pandemic control. Its policies reduced cases faster than in the U.S. or the U.K. but Germany was even more successful, without a lockdown. French officials were less than transparent about early shortages of masks and testing, but the country caught up quickly in those areas.

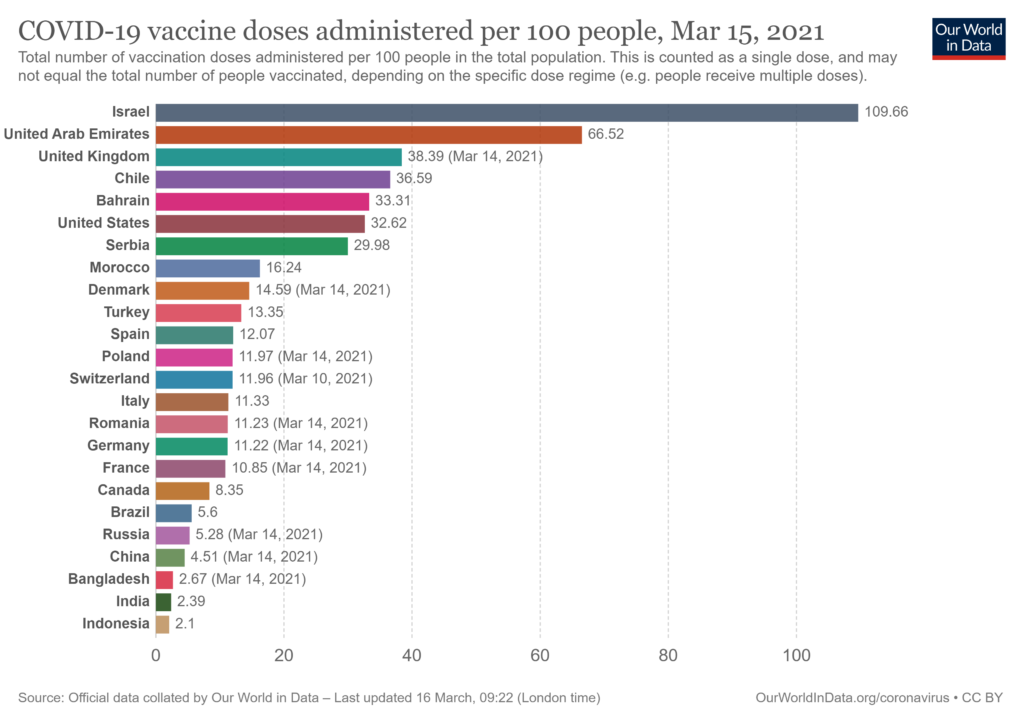

The vaccination program has been a disaster: France is 17th in the world, lagging even behind its European Union peers, in the proportion of people who have gotten at least one shot, according to the Our World in Data website. It may astonish those in the U.S. to learn that their country is sixth, behind another poor COVID performer, the United Kingdom.

To Patrick Weil, a historian and research professor at Paris Sorbonne, France’s COVID failures stem largely from the rise of a class of elite civil servants. Unlike in the past, when engineers and administrators were in government, all now come from the same political-science school.

“There is no diversity of culture,” he said. “They’re all the same.” Macron “should have named a logistics minister. He should have gotten the Army involved. There was a total absence of common sense, it’s been catastrophic.”

It was apparent from the very beginning that the French approach was going to be home-grown. Not so much from the severity of the lockdown that Macron announced — Italy and Spain were already shut up tight but in the minute way the rules were written and enforced.

Anyone seeking to leave home had to self-certify, on a form downloaded from the Interior Ministry, that they were leaving home for any of seven approved reasons. Among them: Exercise, but only within 1 kilometer from home and for no more than an hour. Shopping, but only for “essential goods.” (That wasn’t hard, since most stores were closed anyway.) Work, but you had to have approval from your employer on a separate form. Medical visits, but only if absolutely necessary. You could walk your dog as long as the outing was “brief.” (It was never clear whether dog-walking could be combined with, say, exercise).

Hours of cable news were devoted to explaining the intricacies of these rules. Cabinet ministers appeared on television to answer calls from viewers. “Can I still go on vacation?” one asked the interior minister as the April school holiday approached. The answer was “Non,” and backing it up were more than 160,000 police officers deployed at checkpoints across the country to stop would-be travelers. Anyone caught breaking the lockdown rules was subject to a fine of 135 euros ($160) for the first offense.

Free-market professor and columnist Mathieu Laine, a longtime opponent of the nanny state (France has a few, only a few, such thinkers), says this amounted to treating citizens like children. His new book, Infantilisation, extensively mocks not just the rules but the paternal tone that government officials tended to use in explaining them.

“If the devil is in the details, bureaucracy is his associate,” he wrote. And: “The tone adopted ended up reducing the citizen to a primary-school student to whom a teacher is perpetually giving a lesson.”

However, not only did the containment measures enjoy broad public support, they also worked. France emerged in May from a two-month lockdown with the number of new daily cases below 1,000, from a previous high of 7,000 or so (and in those early days many cases probably went unreported.) Hospitals emptied out.

Cases stayed low all summer, and then they didn’t. But not until late October, when the average daily case figure started to approach 50,000 did the government impose a second lockdown. Same drill: permission slips, travel bans, fines. Spain and Italy tried to avoid similar measures but had to impose some lockdowns at the local levels. Even Germany, which had managed to control the virus through testing and tracing, tightened restrictions on movement.

The French lockdown was lifted before Christmas, even though the number of new cases hadn’t fallen to anywhere near where it was in the summer. It’s been creeping up ever since, despite a 6 p.m. curfew, business and cultural closures and a mask mandate.

Macron, facing public criticism, has been sounding cranky.

“One of the problems with France is distrust,” he said in late January. “There is an incessant search for errors. We have become a nation of 66 million prosecutors. That’s not the way to move forward. Everyone makes errors every day.”

Unsaid, as many commentators pointed out: any apology or mention of his and his government’s failures, the worst of which has been the vaccination program. It is impossible to overstate how badly France, the country of Pasteur, the country that built the world’s best health system, has screwed up. It got off to a slow start and made up for it by vaccinating slowly.

While my friends in the U.S. were getting their shots at motor raceways, sports stadiums, parking lots, gymnasiums and the local CVS, French officials turned up their noses at what they called “vaccinodromes.” Their first priority was old-age care homes, and teams of doctors were sent in – after each potential vaccinee had been interviewed, examined and agreed to get the shot. The protocol for this, Le Point magazine reported last week, was 45 pages long. The cover photograph for the article shows Macron astride a giant snail.

Until recently, hospitals were the only other place one could get vaccinated, despite the fact that France’s 22,000 pharmacies were already experienced in giving flu shots. Nor could individual GPs vaccinate their patients. Both pharmacies and doctors now can do so, but they complain about a paucity of doses. Macron didn’t help matters by saying, entirely falsely, that the AstraZeneca vaccine was “quasi-ineffective” for people 65 and over, shortly before it became available in France. (While the final answer won’t be known for a while, lots of evidence suggests pausing vaccinations was also not science-based.)

“We’ve known since March that a vaccine was coming,” economist Antoine Levy told Le Point. “We should have been ready to distribute them as soon as they became available.”

True, the European Union’s procurement for its 27 members was slow and ultra-cautious. True, France is the biggest vaccine skeptic in Western Europe and there was an argument for proceeding carefully. True, doses have been in short supply from time to time (though as John Lichfield, the dean of English-language coverage of COVID in France points out, the government has received far more doses than it has administered).

At current rates, France won’t reach the herd-immunity threshold of 80 percent of the population until October 2022. Government officials have regularly promised to do better and may finally be doing so, even ramping up shots on weekends.

Now THAT goes against the national culture.

Lead image: American Scholar

Kudos, Anne! Your piece is well researched and written to demonstrate clearly what is, and isn’t, happening in France during the COVID-19 crisis.

Thank you so much! I’m starting to think maybe you were right after all and Macron will indeed lose next year. If that happens, it will certainly be a self-inflicted wound.

Many thanks Anne, for taking my mind to Paris and away from March in Maine.

Yes, shots are moving along here. I just received my first on Sunday but New Hampshire (on the other side of the river) friends in the 60+ category have mostly gotten their 2 doses.

More vaccinations and our new President is certainly lifting our spirits.

Thanks, Tinka! Spirits count more than anything, right?

Thanks, incisive and informative. While we have my sister in law living in Marseille , the big picture I did not know. I do remember them having to go on line to fill a permission slip from the Préfecture to be able to leave their appartement. A great hassle.

Definitely a hassle, though it makes one think twice about unnecessary excursions. Perhaps that was the idea!