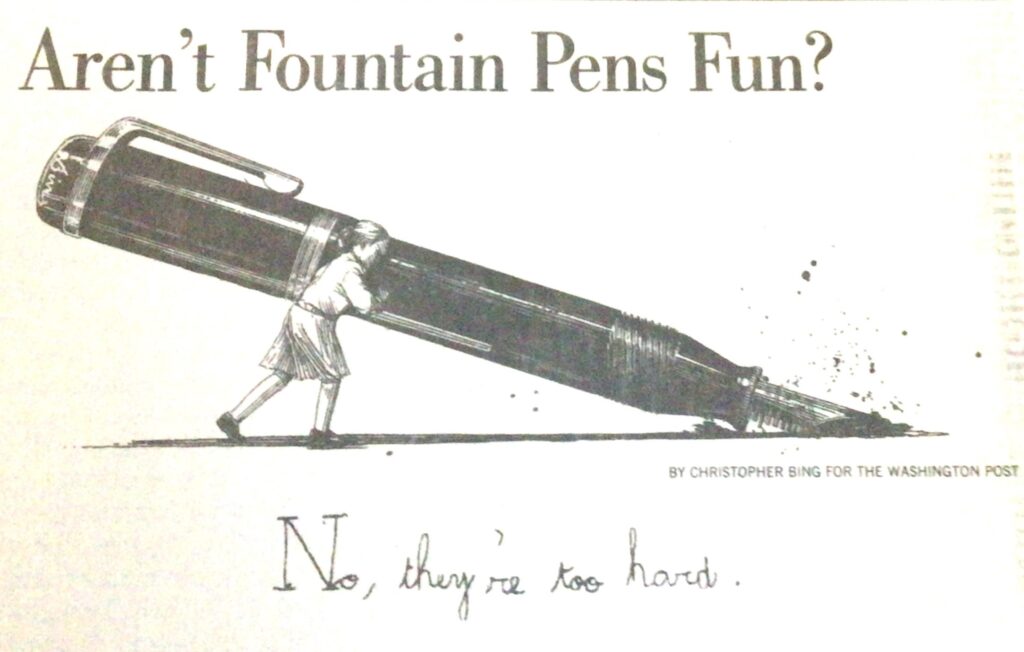

Reprinted with permission from The Washington Post. See below for a response from the grown-up Louise.

October 5, 1997

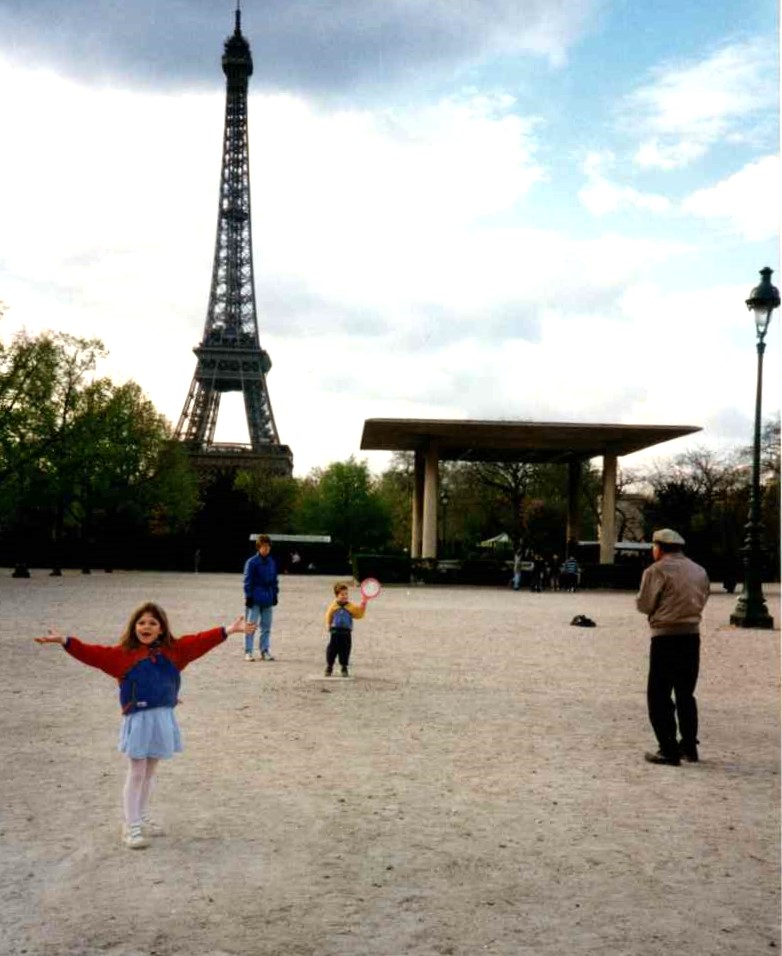

PARIS — Less than a month into the French equivalent of second grade, my daughter has met the enemy and it is a fountain pen.

Wrestling with homework every night is hard enough in this rigid academic system. But wrestling with a “stylo plume”—literally translated, quill pen—makes it even tougher. As I watched Louise bend over her notebook, trying to reproduce the fat o’s and curlicue d’s of the cursive French alphabet, I asked myself whether putting her into a French school was the right decision.

Penmanship itself is graded here, severely. If Louise’s letters drop below the line where they should not, or climb too high, she loses points. It is not enough that words be spelled correctly or that the paper be free of blue blots. Nor is she supposed to cross out a word she writes incorrectly. She must start the page again.

Her teacher often admonishes Louise by writing “Manque de soin” (lack of care) in red ink on her writing and spelling exercises.

Louise accepts this as she accepts much of her difficult work: just another peculiarity of picky grown-ups in this strange new city.

Her classmates, English-speaking and French-speaking alike, struggle with the same rigidities. I bet no child in America had 10 little blotters on his or her list of required fall school supplies. Where their counterparts in Washington classrooms are expressing themselves with No. 2 pencils and using the Internet, Louise and her friends are copying letters, spelling words, memorizing poems, learning the forms of grammar and gripping those unfamiliar pens.

My husband and I chose a French school for our children to give them the gift of a second language. In doing so, we accepted the dry, non-creative nature of the system. Last year, our first in Paris, we all survived school, with some effort. But now that Louise is in second grade, the academic workload is more serious. After two weeks of torture supervising Louise’s homework, I decided to investigate why using a fountain pen is de rigueur.

I found few allies among my fellow parents. Though the minority who are from Britain or North America shared my frustration, the French parents did not. At a class meeting, my question about fountain pens drew blank stares.

“The pen and the fork, our children learn early to use them both,” said one mother. The teacher just shrugged in that pouty sort of way.

Photo: Istock

The fountain pen, it turns out, is embedded in French culture and history. It is emblematic of the roots of French education in the same way the one-room schoolhouse, with pioneer children scratching on their slates, stands for the dawn of American education. In France’s centralized, nationally run educational system, in which the written word is valued above all else, the fountain pen is the key to the gate.

“The blue ink spot on the finger is a badge of French education,” Bernard Cerquiglini, director of the National Institute of the French Language, said cheerfully. “It is the mark of the French flag on the body of the French student.”

Those marks never fade: Cerquiglini said his grandfather, an illiterate Italian immigrant, carried three fountain pens in his jacket pocket until the day he died.

In its refillable version, the stylo plume has been required in French schools since about 1860. Before that, students dipped their pens in little inkwells in their desks. Even in the early years of this century, little yellow Waterman trucks rolled from school to school, filling thousands of inkwells like fuel trucks fill the underground tanks at gas stations. Cartridge fountain pens were later found acceptable, though some people still look down on them.

Photo: ebay with seller’s permission

The idea was that only with a fountain pen would the young student hold his or her hand in proper writing position. Pencils were dirty; the ballpoint pens that came along later were common and deformed the hand.

The cult of the fountain pen is everywhere in this country where, it is said, they buy more pens per person than anywhere else in the world. A typical present for first communion, at age 12 or 13, is often a gold fountain pen, kept for life. The late President Francois Mitterrand turned down the offer of a custom stamp with his signature and spent an hour a day signing documents with his fountain pen. Even typewritten business letters often include a handwritten closing before the signature.

“To have a clean, correct notebook shows an orderly mind, a certain structure ready for work,” said Alain Bouchez, senior inspector for primary education in France.

These days, things are a bit more relaxed. Louise has been granted a roll-ball dispensation for the moment, and is allowed to cross out the occasional word. Her copies of French poems are neater and cleaner, and she seems proud of that.

I have started looking more closely at my own handwriting. It’s so crabbed that most of the time no one but me can read it. But maybe if I bought a fountain pen…..

Louise Responds:

The process of graduating from the ball-point to the fountain pen felt dramatic, and I embraced it—the romance of mindless toil, the frisson of discipline. I remember where I was sitting, at the back of the classroom, the way Madame Junglouthe’s wavy red hair fell neatly over her shoulders, the silence save the scratching of pen on paper as my classmates practiced their letters. I walked to her desk with my copie. As she examined the attempts I had made to stay within the lines, my seven-year-old-body flooded with adrenaline. Looking up with a little smile she said ‘Très bien Louise, c’est bon, tu peux passer à la plume.’ I flew back to my seat, practically weeping with relief.

Writing beautifully was a big part of my childhood, as much because of the content of the article you just enjoyed as its author and her spouse. As you now know, in French primary school, it was not what you wrote that needed to be beautiful, but rather the way you wrote it. My parents did not care whether I had nice handwriting, but they delighted over a show of enthusiasm for writing of any kind, and I was enthusiastic. My journals were feverish and copious, full of flowering prose. I remember asking my dad to edit a middle-school English essay, and standing there while he emotionlessly crossed out every “very” as if it was obvious, as if it wouldn’t affect me at all. The restrained efficiency of English was at odds with the lengthy French sentence. English’s friendly first person, as long as it didn’t begin the paragraph, was cool to use. It competed with French’s evasive author, the illusion of objectivity, the way the form of your writing must stand in for its personality at all costs.

Any nation bestows a great burden on its students. For American kids I think the burden is the illusion that you are unique, special, capable of greatness, and that our nation is capacious enough to notice hard work and reward it. If there was anything that French school beat out of me, it was the notion that I was special (It hurt, but I am thankful). For French kids I think it is simply that the beautiful letters—used the French way—are too heavy, too much of a big deal, too lofty for anyone to reach. How can an “I” stand up under that weight? How can an “I” exist with integrity after the violence of Bernard Cerquiglini’s blue ink stain of the flag on the body of children, like a cattle brand?

I think it’s interesting to look back on exactly how harsh this fancy international school was, and how newsworthy it seemed to my parents and to the Washington Post. It was a relatable harshness, a performance of discipline that made a big show of literally crossing every “t” and dotting every “i.” Then and now, there are children across France for whom the use of a fountain pen is the least of their worries. The national education system fails these children with a rigor and discipline that I recognize from my education, only now it is more practice than performance. The resilience it takes to survive despite being taught that they cannot fit inside the lines, and even if they could, they are illegible, is what feels newsworthy now.

Writing this addendum spurred some research into contemporary French authors who I do not associate with the stylo plume, whose work is outside the lines. My first thought was Virginie Despentes, director of the feminist film “Baise-Moi,” whose series “Vernon Subutex” I adore. I haven’t read any of the following authors, but they come recommended by some French friends of mine who, through the process of texting me, noted that they don’t read French authors much either. Take a look at “Tupamadre” by L. Etchart, “Odyssée des filles de l’Est” by Elitza Gueorguieva, and the works of Annie Ernaux, Marie NDiaye, Édouard Louis, and Diaty Diallo.

Thanks to Anastasia, Clara, and Marie for the recommendations.

llustration reprinted with permission of Christopher Bing and Louise Trueheart. Feature image from Pixabay.

Thank you for this. I think a whole book could be written about French penmanship (per se and also as a metaphor) and how it is anchored in society and how society is anchored in it. A perfect glimpse from the outside (which we all need so much!) The whole notion of not making a faute, or if one does, not showing any evidence of it. Wow. Just in a stroke of ink, but true across so many elements of French society. Brilliant.

Thanks, Polly, and I totally agree! I wonder what the American equivalent of the fountain pen is.

Thanks for this reflection and response. My early schooling was in Germany, where fountain pens were also required. Year later I realized this explains why I was forced to change from being left-handed to right, as the left hand would smear across the wet ink. Who knows how many born lefties were warped by the obsession with fountain pens?

In fact our son says just that. Glad you liked the piece!

Un grand “Merci!” à Louise, qui a bien compris de quoi il retourne…

Merci, je transmets ton message!

You and Louise are a really great joy to read

Aw, thanks Joe!