I’ve written before about how Paris is filled with war memorials, especially for World War II. I was reminded recently that stories also bring that war home to Europeans. At a time when horrible violence is rising anew on this side of the planet, war memories have even more meaning.

In the U.S., people mostly think of WWII connections as how their grandfather or great-uncle fought. And many thanks to them. In Europe, World War II is a lived experience. Every street holds a piece of that history. A five-minute walk from our former apartment on the rue de Lille, for instance, takes you to the German sniper bullet holes in the old Defense Ministry. The rue de Rivoli celebrates fallen Résistants in little shrines whose flowers are perpetually renewed. Times 100 examples, or 1,000.

My rediscovery of this reality began in Paris, where I attended a book presentation by my friend, historian Ellen Hampton, about her most recent book, “Doctors at War: The clandestine battle against the Nazi occupation of France.” She described how French doctors found ways to treat wounded Resistance fighters and soldiers, though that put them at risk of being caught and imprisoned. Even Jewish doctors, for whom practicing medicine was double jeopardy, found ways to treat patients.

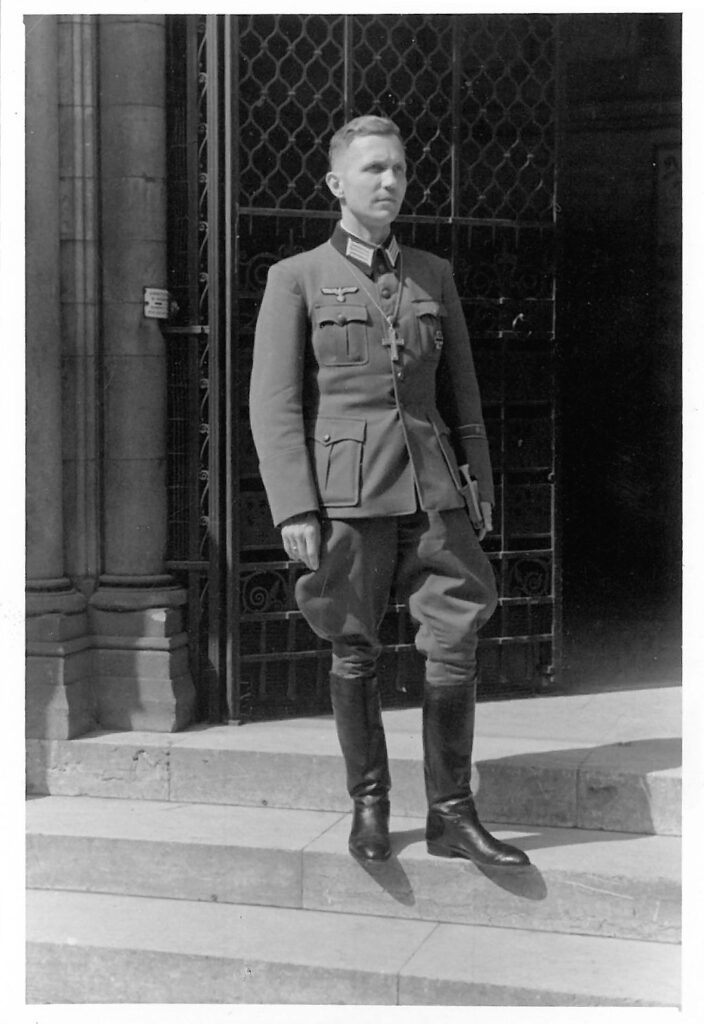

Ellen’s talk was at the American Cathedral in Paris, which Charlie and I have gone to for more than a quarter-century. It has its own dramatic World War II history. During the war, the Cathedral dean fled for the U.S. and organist Lawrence Whipp provided services for the few Americans remaining in the city. He was sent to an internment camp after the U.S. entered the war in 1941 and the Germans took over the church. (Whipp survived and returned, only to die later under mysterious circumstances.) A Lutheran pastor, Rudolf Damrath, held services for German troops. And preached against dictators and evil, even after warnings from his superiors.

American Cathedral Archives

I had heard this story for many years, but entirely from the French and American sides. Then a few years ago a German-speaking American priest, Archdeacon Walter Baer, researched Damrath’s story, learned the extent of his resistance, wrote an article about it and invited Damrath’s daughter, Maria Luise Damrath, to come to Paris and speak to us. It was a thrill to see this live piece of history. Walter’s article can be found here, starting on page 15, along with an article about Maria Luise’s talk.

Then Charlie and I went to Berlin to see Louise. By chance, I found more personal connections to the war. We were met at Brandenburg Airport by Louise, on the right, and her partner, Soph. They were driving Louise’s car, which has been christened Bob Champagne.

Over dinner, Soph talked with us about how their family in southern Germany had lived during the war. Most notably, their grandmother’s uncle, a priest in a small town, ran youth activities for the local church. He scheduled those activities for the same time as the Nazi youth regularly met. The hope was to keep some of those young people away from Fascist propaganda, but he was told to end the schedule conflict.

On our last day, Louise and I went to the German Resistance Memorial Center, in the very building where a group of high-level army officers had planned a coup to assassinate Hitler in July 1944. The bomb failed to kill the Führer and the officers were shot in the courtyard.

The second floor of the museum devoted a lot of space to lionizing the military officers, civilians, religious leaders and others who had tried to resist the horrors of Hitler’s rule. More meaningful to Louise and me was the third floor, which highlighted Jewish resistance to the Nazis, in Germany and in other countries.

One display was of Jewish fighters in western Poland, now Belarus, where partisans battled in the forests around Minsk. They rescued captive Jews, fought Nazis, destroyed rail lines and the like. There was a photograph:

The display brought back something I was amazed I had forgotten: More than 30 years ago I had met two people who had done just that: They had been Jewish partisans around Minsk.

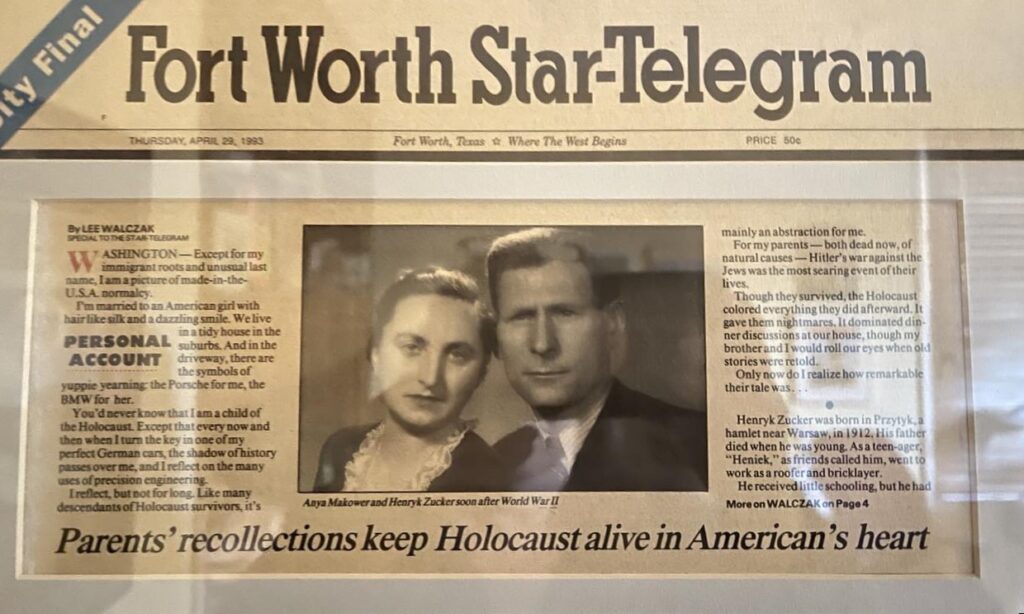

They were Anna and Henry Walczak, parents of my friend Lee Walczak. I met them at the 1988 wedding of Lee and my friend Maria Recio, whom I had met when we all worked at McGraw-Hill/BusinessWeek. The parents died years ago and sadly, Lee died of cancer in 2008.

Maria and I had remained close. I messaged her the photo, and was amazed when she said the fighter in the back row, fourth in from the right, looked like Lee’s father. She sent a photo of a story Lee had written years before about his parents’ history.

Courtesy of Maria Recio

The story describes how the couple, then Anna and Henryk Zucker, placed their young daughter in an orphanage and went to fight because they felt the cause was too important to simply flee. After the war, they went to find the girl but the orphanage was gone and there was no trace of her. Their immigration journey, during which Lee and his brother were born, eventually led them to Maryland.

It’s not clear whether Lee’s parents were in the unit in question, or whether the photograph in the museum is of Henryk. But it brought home to me again how little separates us from the horrors of war, fascism and prejudice, especially today.

Feature image: Jack Downey, U.S. Office of War Information, Library of Congress

Resources:

Cameron Allen, The History of the American Pro-Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Paris (1815-1980)

David Drake, Paris at War, 1939-1944

Charles Glass, Americans in Paris: Life and Death Under Nazi Occupation

Delightful!

Merci, Don!

Thank you Anne for this article. I have read a lot of books about World War II (and WWI which was a large cause of WWII) but it is nice to read the more personal stories as well.

Thanks, Kay, I’m really glad you enjoyed it!

Have you read Bilger Burkhard’s recent book, “Fatherland”? Seems on point given the French WWII experience (particularly Alsace). Worth your time if you haven’t.

As it happens, I’ve read Robert Harris’s book “Fatherland,” a Berlin-based detective novel based on the premise that the Nazis won. Not quite the same thing, I realize. I’ll check out the one you suggest.

A great time to remind folks of the history behind today’s conflicts.

Thank you so much, Amy.

An especially timely post for me, as I today concluded a brief stay in Paris with a visit to the Musée Nissim de Camondo, built at 63 rue Monceau as the home of a prominent, immensely wealthy and (so it seemed) privileged family.

A plaque reveals the family’s fate: “Mme Léon Reinach née Beatrice de Camondo, ses enfants…et M. Léon Reinach déportes en 1943-1944 sont morts á Auschwitz.”

My thanks to Charlie to introducing me to their story and memory of them through two remarkable books by one of their descendants, the English artist Edmund de Waal. (“The Hare with the Amber Eyes,” and “Letters to Camondo.”

Thanks, Robert! Another good book about that topic is James McAuley’s “The House of Fragile Things.”