In my 25 years in Paris, I’ve always resisted the temptation to declare the city “empty.” Not in August, not during the pandemic. No matter how many people have fled or can’t enter, there were always enough residents and visitors to occupy the cafés, shop at the open-air markets and throng the Champs-Elysées.

Not this year. A double whammy of escaping Parisians (many of whom stayed around last summer for fear of the virus) and non-arriving tourists has gutted many parts of the city. Here unexpectedly for the summer, I’m getting the full experience – or should I say the empty experience?

Walking or bike riding through Paris these days is rather like watching the Tokyo Olympics: The absence of spectators takes away some of the shared excitement, but also gets you closer to the essential. On television, I hear the horse inhale as it jumps and the soccer player call to her teammate. In Paris, I focus on the flowers in the park because I’m not distracted by the crowds on the benches. The sudden buzzing of a motorcycle sends a pigeon flying into the air and I’m struck by its arc. A vacant traffic circle on a cloudy day sparks meditations on the possibilities of open space.

It’s hard to measure just how deserted Paris is, but I’ve never before seen available seats in cafés on the Champs-Elysees in the summer. Vaccinated foreign tourists are allowed to come to France now, but many chose not to. In other years, I’ve had to breast-stroke though the crowds just to get down the sidewalk.

Rides at a seasonal amusement park in the Tuileries Gardens, typically mobbed, were starved for customers.

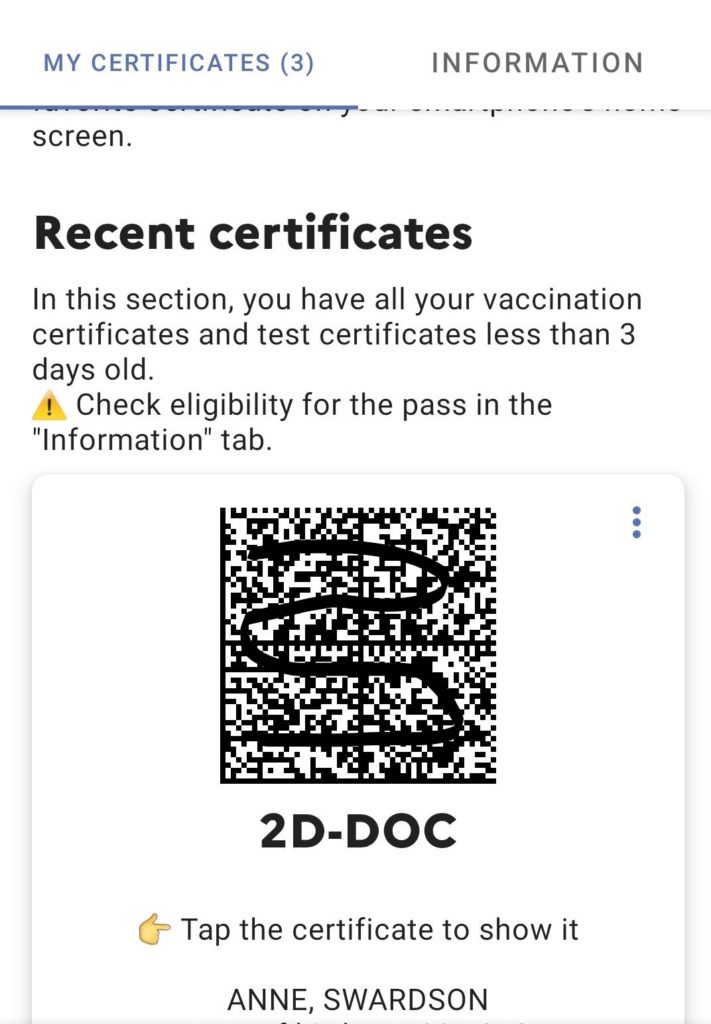

It’s not just the absence of people. Some who are here can’t go to public places because they don’t have the negative COVID test or vaccination proof required to get in. President Emmanuel Macron made a smart move when he required a health pass for bars, restaurants, museums – and amusement-park rides – but the government has been slow to help foreign visitors convert their own vaccine proof into the QR code we all carry on our phones here.

The people who remain in Paris aren’t tempted to venture out, deterred by the chilly, rainy weather. France’s neighbors, meanwhile, are undergoing heat waves, forest fires, mudslides and floods, all seemingly related to climate change.

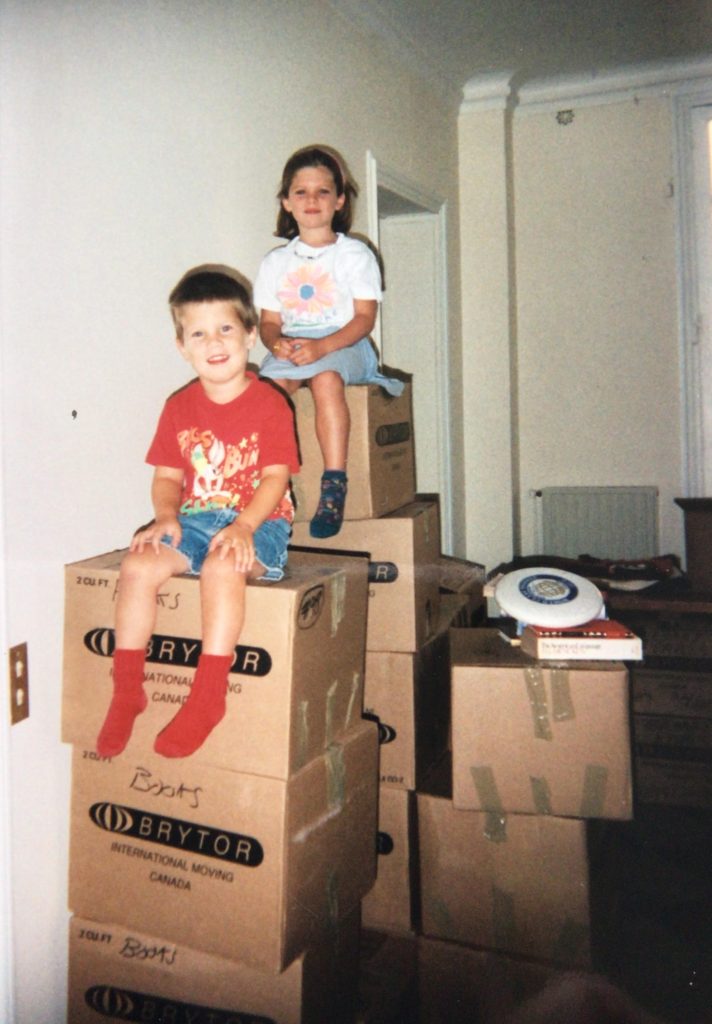

On Aug. 15, the Truehearts – me, Charlie, Louise and Henry – celebrate our 25th anniversary of moving to Paris. That night in 1996, we ate at a bad café, thought the food was delicious and didn’t even look around to see how full it was. We didn’t know this city was going to become home, even though Charlie and I had desperately lobbied our employer to send us here.

We quickly realized it was where we wanted to be, though it took our friends and family longer to get that.

“When are you going to move *back*?” they would ask us. Back to what? Paris was and is home. Even deserted, it’s where we belong.

And even now, with so few people around, empty is relative. On the market street where I usually shop, a few stores, defiantly, are open all summer. Among them are the Big Five: Butcher, Baker, Fishmonger, Produce and Cheese. “We are here for our customers during the year. It’s not right to desert them in the summer,” the proprietress of this unimaginatively named cheese store told me.

Though the outside stand seems to be closed every day.

Also in Paris: Close and dear friends who are here for us, to take walks with or have drinks with or discuss the meaning of life. Emptiness isn’t about crowds in the cafés or cars on the street. It’s what you feel when you aren’t lucky enough to have those connections.

Lovely piece, Anne.

Thank you so much, my fellow empty-Paris resident.

Great post!! Love to you guys.

Many mercis, Bruce, I’m so glad you liked it!

Anne, another wonderful post! THAnk you! Best, Joan Johnson

Thank YOU, Joan! Best wishes.

Happy anniversary, Anne and Charlie. I know the feeling of having found home. We’re fortunate to have gotten you.

That’s so nice, John, many thanks! From one old-timer to another.

Hi Anne,

I think I would enjoy the empty city, especially after a month in Nantucket where it takes fifteen minutes to get through an intersection. I’m happy to be in Vermont where things are a bit saner. I do, however, dream of being back in Paris.

Best,

Winky

Hope to see you here some time soon!

Speaking of old-times, Karen and I will celebrate 40 years in France on September 15th!

Congratulations, old-timers!

Very interesting. I’ve experienced Paris in August a number of times and enjoyed it, most recently in 2019. On our walks, we avoided crowded places like the Louvre or the lower Latin Quarter. Some of the very quiet streets with shops and cafes closed for vacation were a bit disappointing, but still there were enough businesses open. I hope Paris street life fully revives in September!

I agree, and thanks. Let’s just hope that the revival of street life in September doesn’t include more anti-health-pass demonstrations!