I took a train to vote in the French elections. But it’s not as simple as that.

For starters, I was in Virginia. Second, France has never seen an election like this one.

The chaos began when President Emmanuel Macron dissolved the French parliament on June 9 after his party suffered a big defeat in elections for the European Parliament. He called a snap election, with the first round of voting scheduled for June 30, to constitute a new assembly. More below on what an incredibly stupid move that was.

For me, a naturalized citizen since 2009, it was also inconvenient. We were scheduled to leave Paris for the U.S. on June 17, but I also wanted to vote. Marine Le Pen’s far-right party won more votes than Macron’s centrists in the European elections and was leading in the polls. Every rational citizen’s ballot was needed to fend that off.

However, France doesn’t allow absentee ballots, early voting or mail-in voting. The only way to vote outside of your assigned polling place on the day-of is by proxy, and a strange form of proxy at that: You ask a friend to vote for you and state your choice. Then you go to your local prefecture (an administrative center), show your national ID and give the name and ID of the friend.

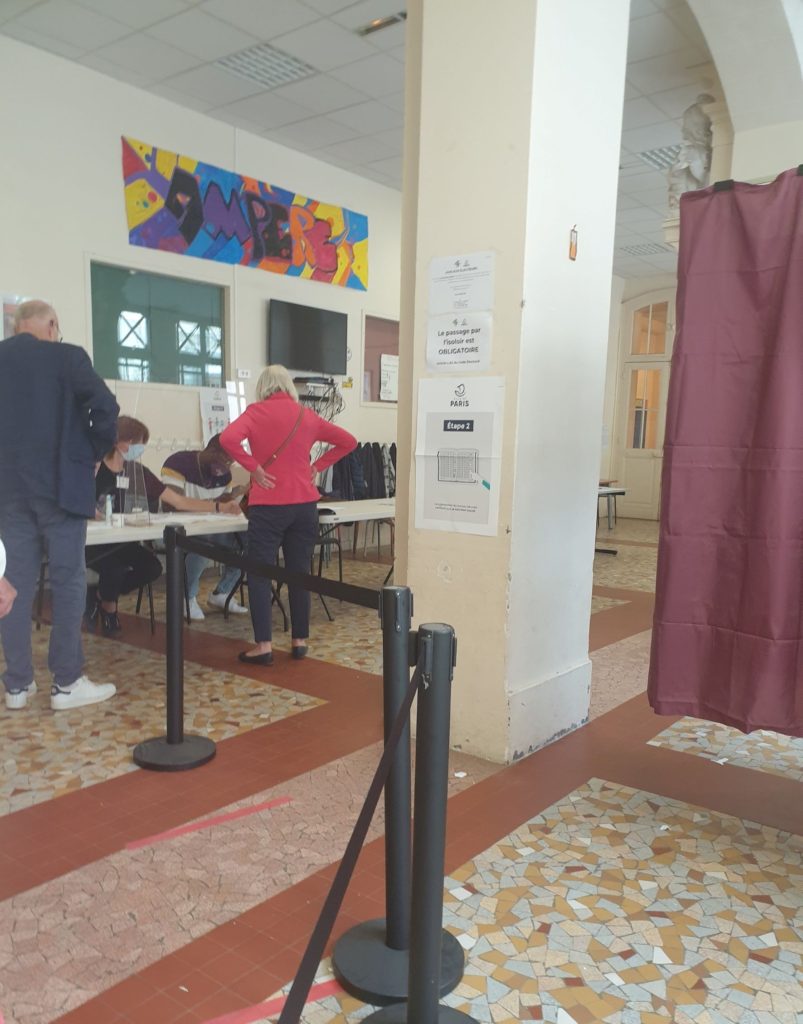

On Election Day, if you live in Paris, this nice friend votes at their own polling place, then crosses the city and votes for you in yours (unless they already vote at the same place as you, which is even easier). In a nation obsessed with privacy, where voting happens behind curtains, it seems weird to be required to reveal one’s preference to a friend in order to vote.

Voting in 2021

We had done it before and it worked fine. But this time we were frantically rushing around getting ready to leave town. I looked on the prefecture web site and saw that, because of the special nature of this hastily called vote, doing the entire process was possible online.

I didn’t realize until arriving in Virginia that I’d missed a key point. You can sign up to use a proxy—it’s called a procuration — online. But you have to prove your identity in person, at the prefecture. It was a long way back to the 17th arrondissement.

I got to work. A friend who already voted in the same polling place as we did agreed to be my mandataire, as it’s called. I was able to sign up and enter her in the online system. (You can meet her at the end of this post.)

The consulate in Washington was the only place where I could do the identity-proving part. I made an appointment online for several days hence and bought a ticket on an Amtrak from Charlottesville.

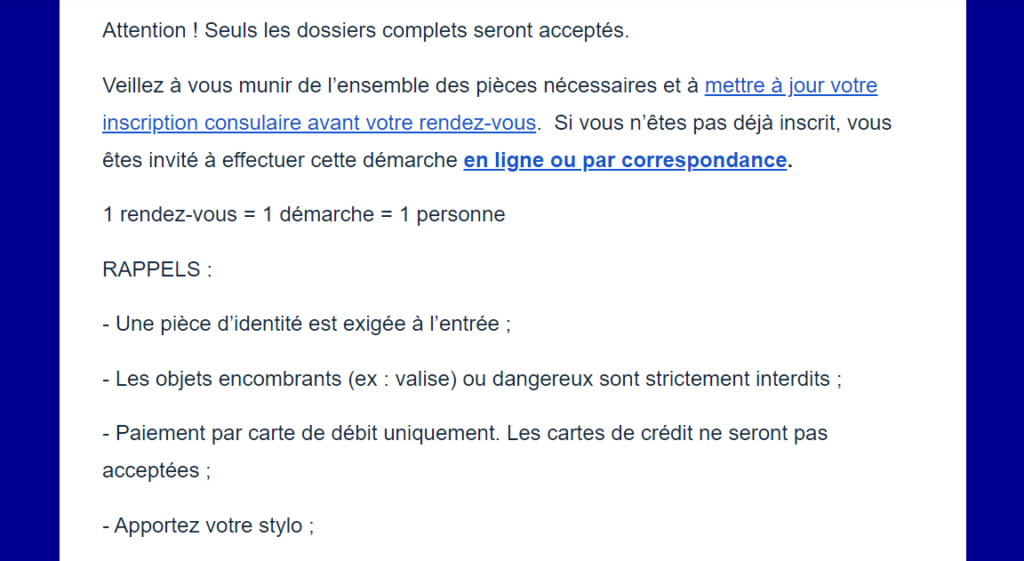

The consulate took my appointment very seriously. I received several emails ahead of time telling me what I needed to do (arrive 10 minutes early), bring (my ID, my mandataire information and my own pen (the email didn’t say whether it had to be a fountain pen)) and pay (debit cards only).

Why go to all this trouble? Because this may be France’s last chance to blunt the impact of the far-right National Rally party, and a smaller and even worse party whose founder believes in the “Great Replacement.” The National Rally has softened its positions over the years but still pushes draconian immigration restrictions, limiting some benefits to citizens only and refusing to recognize Muslims as equal citizens. Not to mention the party’s distate for the European Union.

Its 28-year-old leader, Jordan Bardella, who looks like he was squeezed out of a toothpaste tube, would be in a position to become prime minister should the Rally capture an absolute majority of parliament. (In France’s hybrid system, the president retains power over defense and foreign affairs, while parliament deals with domestic issues. When the president and prime minister come from different parties, it’s called cohabitation.)

The left, meanwhile, has organized itself into a broad coalition—remarkable for such a fractious group—with a program combining high spending, restrictions on layoffs (France’s unemployment rate dropped to its lowest rate in years after Macron pushed through more labor flexibility) and a freeze on consumer prices (how?). The party also has had several outbreaks of antisemitic remarks among its leaders.

Why would Macron do something so idiotic as to bring this on? The European elections did nothing to change his working majority in parliament, which he could have kept for the last three years of his term. He said he couldn’t govern when the people were sending such a clear signal of dissatisfaction. Why he thought national elections would produce a different result is hard to imagine. His group is third in the polls; the Rally leads with as much as 36% support.

Vous trouverez plus d’infographie sur Statista

Vous trouverez plus d’infographie sur Statista

Some of the best explanations of this madness come from John Lichfield in The Local, Lee Hockstader in The Washington Post and Roger Cohen in The New York Times. An excellent thread on Twitter (in French) chalks it up to four factors: Macron’s “savior complex,” his failure to consult advisers and his belief, unsupported by evidence, that a silent majority supports him. Plus, the French constitution lets presidents do pretty much anything they want.

Hence the importance of voting. The only difficulty at the embassy was finding the office where I was to be accepted, in the multi-building, high-security complex on Reservoir Road. The actual approval took maybe 30 seconds and fewer than half the documents, cards and code numbers I’d brought with me. I didn’t even have to sign anything with my pen or pay for anything with my debit card.

I asked the young bureaucrat whether they’d had a lot of approval requests like mine—bear in mind that French people who live overseas don’t use this process but instead vote live at their respective consulates. (They also have representation: 11 of France’s deputies in the lower house represent overseas constituencies. Good idea.)

She smiled and said yes, people were coming every day. From far away, like me? I asked. She didn’t know, she said, but she did have someone from Baltimore the other day.

I was one of more than 2 million French men and women who set up procurations between June 10 and June 26, twice as many as the presidential elections in 2022, the Interior Ministry says.

Plus de 2 millions de procurations établies à 4 jours du premier tour, deux fois plus qu’en 2022

Le ministère de l’Intérieur a annoncé ce jeudi que 2 124 918 procurations ont été réalisées entre le 10 et 26 juin

➡️ https://t.co/PODZIY4Zzu pic.twitter.com/waMGyXAtmQ

— Le Parisien (@le_Parisien) June 27, 2024

That’s 2+ million other wonderful people who are willing to serve as mandataires.

Mine is Anna, a 21-year-old family friend who said she was happy to help.

Thanks for supporting democracy, Anna!

very cool story

Thanks!

I hope everyone will be inspired by your herculean effort to vote in the French elections, and will vote wherever they can. It can’t be as hard as it was for you. As a French citzen whose residence is in the UK, I had a much easier time of it. With my elector number and my NUMIC, the ID number by which I am known to French authorities in the UK, I received an email with a special voter ID number for this election, a week later a text with a password. With these four items, and my response to a verification text after I voted, I was happy to see that my vote was in the “urne” a few seconds later. Why NY state can’t figure out something similar is a mystery to me, the origami exercise we have to go through is ridiculous, not to mention having to rely on the unreliable Royal Mail and USPS. There has been talk of changing this …. BTW, if we vote in person it isn’t at the consulate but in the Lycee Charles de Gaulle (very close to the consulate).

Macron called the election to avoid swimming in the Seine before the Olympics. I’m doing a swim in his stead on July 4. Please send your mandataire.

As long as you don’t use a mandataire!

I was a little stressed about finding a proxy myself: I’ll be absent the weekend of the second round. I asked a friend, but she said I was the third person who’d asked her. And each person can only accept 1 mandate. Fortunately, the stars aligned and her other friends found help elsewhere. I admire your own dedication to guaranteeing your vote.

I wrote a few words myself about the upcoming election, from my perspective as a British-French dual national: https://medium.com/@bchadwickfrance/a-tale-of-two-elections-645f0d185f76

Thanks Anne, and thanks for making the effort! Intense times alright!

Pat

Félicitations, Anne!

I appreciate your perspective — and commitment to voting! — for such an important election. We have an important one coming up in the U.S., too. I hope Americans who support democracy are as dedicated as you were.

Many thanks and yes, I hope so too!

I’m a little late to comment but a hearty thank you for your commitment to exercising your mandate! As I frequently say: if you don’t vote you forfeit your right to bitch afterward.

I dunno, bitching can be so much fun!