For one of our first Thanksgivings in Paris, we invited a few French friends over for dinner. We made a few mistakes.

One was to assume everyone knew what it was all about. One friend arrived with several bags filled with beautiful presents for the children. When we protested, perhaps overly, that she shouldn’t have, she responded: “But isn’t that what you do?”

A second was not to make clear that it was essentially the only meal of the day. When a family arrived as requested at 4p.m., they looked in dismay at our carefully laid dining-room table. “Oh dear, did you have lunch?” I asked. They nodded a little bleakly.

Then I tried to explain the Thanksgiving story, or at least as we told it 25 years ago, to the young people around the table. I don’t know if was my French, but they quickly lost interest, including my own children.

In the end, everyone had a good time. And over the years, Thanksgiving customs have become better understood here. The butcher on the rue Cler, a market street in the 7th arrondissement, posts a sign every year reminding customers to order their turkey. I’m at a loss to explain the apostrophe.

That doesn’t solve all problems: Many French ovens are too small to fit any size turkey. On the other hand, the butcher will usually spatchcock it for you.

Over the years, we’ve celebrated Thanksgiving in various ways here. A dear friend, now deceased, used to invite us to the Traveller’s Club on the Champs-Elysées. A relic from the days when expats mostly hung out with each other and it was OK to keep women from joining, the place nonetheless produced an elegant version of the standard menu.

Some restaurants, such as the Café de Mars, offer special Thanksgiving dinners as well.

Paris used to have several stores that sold Thanksgiving products, such as Caro syrup, canned pumpkin and cranberry sauce, to expat buyers. There was even one shop called Thanksgiving. It closed in 2018, and some of the others have cut back as regular French grocery stores offer a wider array of American products. Marks & Spencer (OK, it’s British, but there are multiple stores in Paris) has cranberry sauce, and some restaurants deliver Thanksgiving-style meals.

That’s a good thing, since all restaurants have been closed for dining since this second lockdown was imposed at the end of October. Many are trying to do business at the front door, but I can’t imagine they get many customers.

All kinds of other stores are doing the same (I thought they were supposed to be closed, but I must have missed a footnote in the rules. For some reason, this service is called “Click and Collect” (as opposed to “cliquez et récupérer,” which I believe is what it should be in French).

Happily, all stores will be able to open as of Dec. 1 as part of France’s gradual emergence from lockdown. On Dec. 15, people will be able to leave their homes and circulate freely. So during the interim two weeks, how can you go to a store? As always, just fill out that handy-dandy certificate, downloadable as an app on your phone.

We do have a lot to be thankful for, here and across the ocean. The virus is receding in France, thanks to the lockdown, though more slowly than one might wish. The U.S. election results give hope to Americans – well, some of them – and Europeans alike. Vaccines are on their way.

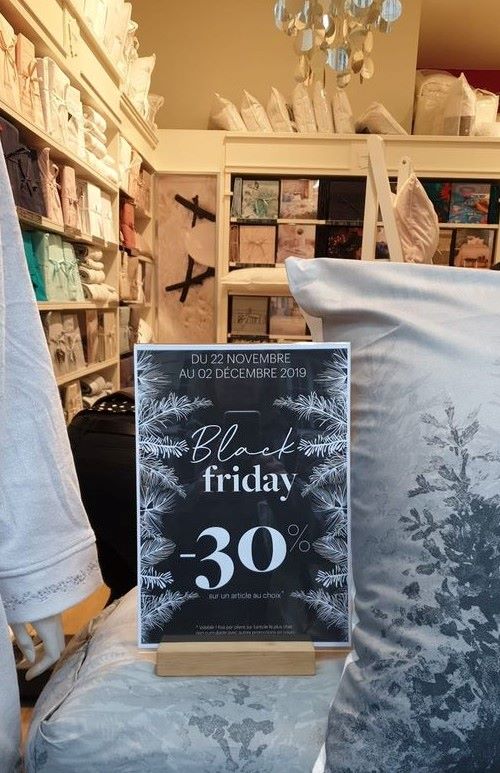

And if shoppers in France have a pent-up urge to shop, there’s always Black Friday. In the past, the dates have been a little variable.

This year, though, it will take place on one specific day: Dec. 4. It had to be moved because stores were still shut by the lockdown on the day after Thanksgiving. In other words, instead of coming a day after a holiday that most French people still aren’t aware of, Black Friday comes a week after that.