In late 2005, I was invited to be a panelist on an evening news show called Mots Croisés. The topic was the riots across France in the low-income, predominantly Muslim ethnic suburbs that surrounded big cities. There were about 10 participants, representing every political party, as well as people from journalism, law enforcement and intellectual circles.

Not one came from those suburbs or any of the many associations that fought or spoke for France’s ethnic minorities. When I brought this up on the live, hour-long show (as the foreign-correspondent talking head I was permitted two comments), there was an embarrassed silence. Like, Why would we invite them? A few people muttered about community-policing efforts and that was it.

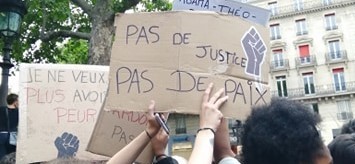

I wish I could say things have improved for France’s minorities since then, but they haven’t. Not economically, not politically and, most important, not in terms of equality. Others have written about those issues, as evidenced by the recent demonstrations against racism and police violence, better than I can.

Photo: Lily Manning

James McAuley of the Washington Post explains France’s seemingly baffling refusal to collect any data on race or ethnicity (spoiler alert: the pretext is that because everyone is treated equally such data would single groups out). John Lichfield unpacks the question of police racism in The Local. Adam Nossiter writes about the political implications for President Emmanuel Macron in the New York Times; Norimitsu Onishi shows how France is grappling with race. In The New Yorker, Lauren Collins profiles a key activist, whose brother died mysteriously in police custody in 2016, with the French version of Black Lives Matter.

I didn’t write a lot about race and ethnicity in France during my time as a journalist at The Washington Post and Bloomberg News, though I was proud to have generated and produced this story by Angeline Benoit about the one exception to France’s absolute refusal to embrace affirmative action. (Why reject affirmative action when discrimination is so clear? See spoiler alert, above.)

For me, the low-income parts of Paris and the bleak suburbs around it were more of a personal experience. When my son Henry played the equivalent of Little League baseball, his team had its winter indoor practices in a gym in a neighborhood called Goutte d’Or – Drop of Gold. We’d walk to and from the Métro through markets selling plantains and manioc, past stores selling food from Morocco, Yemen, Cameroon, you name it. I blogged about how this neighborhood was tolerating the lockdown here.

I went back to the Goutte d’Or often. I took visiting American friends there to show what a real Paris ethnic neighborhood looked like, as opposed to the no-go-zone label that Fox News gave it after the terrorist attacks of 2015. (As can be seen in the video, French satirical TV had some fun with the idea as well.) The rue des Poissonniers (Fishmongers’ Street) is the setting for the conclusion of my never-to-be published mystery novel. That’s also where I was scolded, and rightly so, by a Black fruit vendor for not saying “Bonjour” before I asked the price of his produce.

I went to the suburbs as well, at least one of them. I was part of a team from church that taught computer skills to residents of Le Blanc Mesnil, north of Paris. We met every Saturday at a community center. The students were mostly older. Many had computers at home, but their adult children wouldn’t teach them how to use them.

Email gave them the power to communicate with family in such countries as Togo, Mali and Tunisia. Once, I was instructing three women from three different countries in how to send emails to each other. When the first one landed, after many frustrating attempts, they high-fived each other.

Does this sound like virtue-signaling? It is, albeit for relatively little virtue. For many years I styled myself as someone who really knew these areas, who really understood the problems of the residents. Because I had, you know, been there. More than one time! I had done research! Talked to people! Spoke good French!

My expat friends and I would scoff at the ridiculousness of the burkini ban, or the outrageous harassment of the first student body president of the Sorbonne to wear a headscarf, or the lack of Black and brown guests on French television. But, at least in my case, the words stopped there.

Only with the COVID-19 lockdown and its many examples of brutal treatment of ethnic minorities by the police in the name of document checks, and the subsequent demonstrations about racism in France after the killing of George Floyd, did I start thinking about what I knew and what I didn’t know. It’s one thing to see France’s pretense of a color-blind society as the fraud it is. It’s another to do something about it.

Rokhaya Diallo, a journalist, filmmaker and anti-racism activist of Senegalese and Gambian parents, grew up in a diverse neighborhood in Paris. When she was an adult doing advanced graduate studies, she began noticing that whites viewed her differently. They would ask where she was from “before” Paris, for instance.

“There were no images of women like me in films, or in the media, and that was why people didn’t see me as being part of the national fabric,” she said. In the media, “Either we were invisible, or we were covered as problems.” She was speaking on “Pandemonium U,” an excellent series on Zoom and YouTube run by journalists Pamela Druckerman and Simon Kuper.

In my blogging and other writing about France, I’ve focused on my outsider status – neither native nor expat, neither at home nor uncomfortable. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that the French word for foreigner, étranger, is also the word for stranger. But how bitter it must be for someone like Diallo, who is more French than I ever will be, to know that I and people like me have a built-in advantage that only radical change can tear down.

Lead image: Lily Manning