When a French person tells you’re they’re going to “Paname,” they don’t mean the country. For reasons that are in dispute, Paname is a slang word for Paris.

While Charlie and I didn’t travel to Panama-the-country by mistake, we enjoyed seeking out the many French connections of a nation long linked to the United States.

The most notable, of course, is the spectacular failure of the French effort to build a canal through the 50-mile isthmus starting around 1880. It was led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, the builder of the Suez Canal, who had trouble understanding that Panama was neither flat nor sandy, as Egypt was. Digging through and reshaping Panama’s mountains was an entirely different challenge.

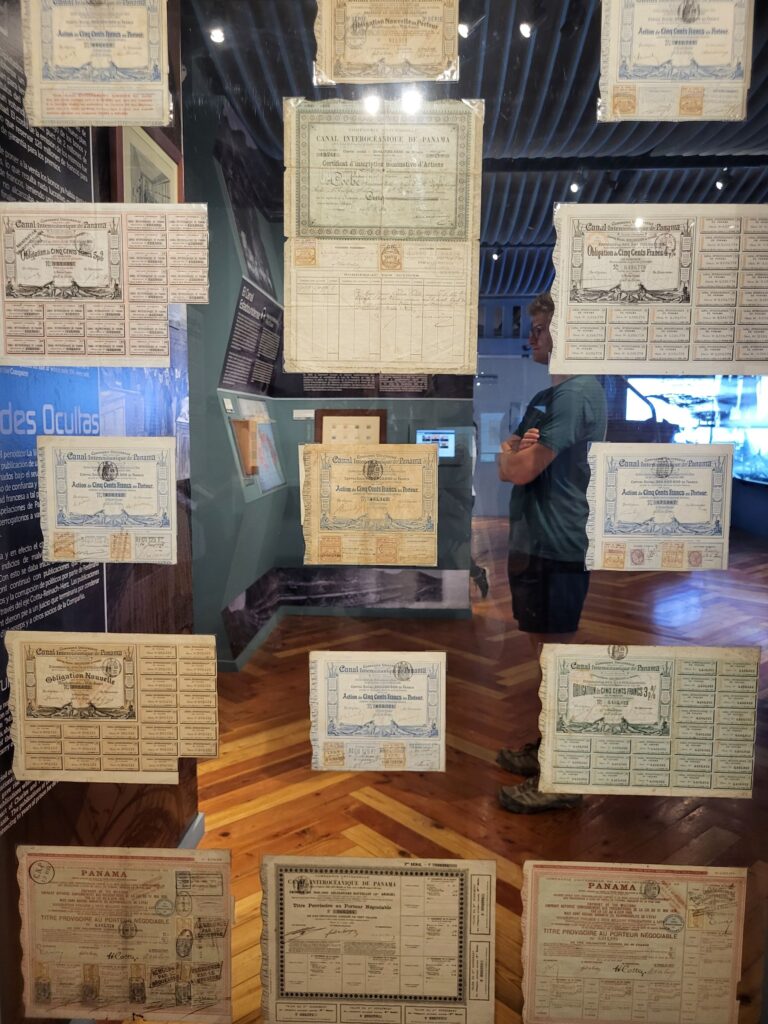

As David McCullough tells it in “The Path Between the Seas,” the failed initiative killed some 22,000 workers from disease (the French also didn’t understand how mosquito-borne viruses like yellow fever spread) and construction accidents. Thousands of investors lost their savings (incredible as it may seem in the France of today, the government wasn’t involved in the project) and De Lesseps, thoroughly discredited, only escaped prison because of his advanced age.

Before reading this wonderful book, Charlie and I had known so little about Panama that we were amazed to learn that the country basically runs east-west and the canal almost north-south. (Speaking of Charlie, anyone who wants to know about the next time the U.S. stepped in after France failed should read his forthcoming book, Diplomats at War: Friendship and Betrayal on the Brink of the Vietnam Conflict.)

In the case of Panama, unlike in Vietnam, the Americans pulled it off. After much machination and lobbying, much of it done by a Frenchman, the construction rights were secured. There was also the revolution, in which the U.S. did or didn’t foment a movement to make Panama, then a province of Colombia, into a country. And a building effort that cost $352 million (using the dollar’s value back then), moved 232 million cubic yards of dirt and rocks and killed another 5,600 workers after the French losses, almost all of them Black West Indians.

The first ship sailed the entire length of the canal, through its three multi-step locks and 21-mile-long man-made lake, on August 15, 1914.

Photo: Souvenir postcard

So the first item on our agenda, after walking around Panama City’s charming old quarter in 90-degree weather, had to be a canal tour. That morning, we took a bus north roughly to the canal’s halfway point and boarded the Pacific Queen with perhaps 100 other people.

The canal looks initially like a river, but closer scrutiny shows how well-maintained are the banks, not to mention the security barriers, lighting and maintenance facilities along the way,

When time came to enter our first chamber at Pedro Miguel, I was astonished to see our neighbors included not just an enormous bulk carrier to the rear but two sailboats of maybe 40 feet each. They tied up onto our ship each time as the water level fell in our chamber, perhaps to keep them from moving around.

There certainly wasn’t room for them to tie up to the Bahamas-registered Makra, looming behind us.

In the lane next door, the cruise ship moved on its own path since there was no room for it to share with anyone.

Fifty percent of the water ejected from its lock chamber was sent into ours as part of a conservation effort — the lake’s level has fallen from a normal 87 feet above sea level to 81 feet because a recent drought and the El Nino weather pattern. The canal accepts as much as 40% less traffic than it used to and we could see lines of huge ships clustered at the south entrance as we steamed into the Pacific Ocean.

De Lesseps and his countrymen have not been forgotten. The Panama Canal Museum details the travails of the French team, including actual worthless bonds from the era. No one who has ever worked for Bloomberg could fail to find these fascinating.

And at the Plaza Francia at the southern tip of the old quarter, an obelisk with a rooster on top and five busts on pedestals honor those who tried.

The French embassy is on the other side of the plaza. It will surprise no one who knows France that there was no sign indicating its opening and closing hours.

Marguey’s family, the Sellers of Philadelphia, supplied the critical, heavy machinery used to build the canal.

Wow! A lot of the big components were made in the U.S. — the enormous lock gates were manufactured in Pittsburgh and floated down the Ohio and then the Mississippi to be loaded onto the ship.

Great piece. You might also want to read the (rather self-serving) “Moi, Ferdinand de Lesseps” by his grandson (ex buddy of mine..) named Alexandre de Lesseps.

Sounds interesting, and thanks!

That sounds like a truly fascinating voyage of discovery. Let’s get together in Paris or Burgundy when you return.

That would be lovely, and thanks!

Your brief description of the failed French effort under De Lesseps, and the collapse of the “Paname” bonds was enjoyable.

Merci!

Amazing report!

Thanks so much!

Thanks for the plug, sweetheart!

You betcha, babe!

Thank you! Another wonderful blog post! And i will find Charlie’s book on Amazon. Or order it from my Andover bookstore! Hope things are goingvalong alright forvyou both!

Thanks so much, Joan!