There is a genre of French film that rarely crosses the Atlantic but is very popular here. The theme: the hell of the workplace and the nightmare of layoffs.

I count at least 15 movies on that topic in the past few decades, most featuring laid-off employees fighting back against management or, occasionally, middle managers under pressure from both sides. (A list of the films is at the end.)

Similarly, French national-television news often carries layoff stories about what to American journalism would be local fare, such as a factory closure that will cost 200 jobs. France’s finance minister in 2020 spoke up against potential layoffs at carmaker Renault before they’d even happened. Managers are often kidnapped and held hostage by employees – I am not making this up – to protest job cuts.

In a way, this horror of layoffs is no surprise. France’s strict labor laws make it extremely difficult to reduce the workforce – and thus make employers reluctant to hire. A layoff here is a personal disaster that’s even worse, I’d argue, than in the U.S.

Which helps explain why the French are so adamantly opposed – by about 70% — to President Emmanuel Macron’s plan to raise the full retirement age from 62 to 64 to shore up the system’s finances.

Waves of one-day strikes have happened across the country and, contrary to normal practice, all of the major unions are participating, not just the Communist and far-left ones. A nationwide strike is scheduled for March 7 and unions are starting to talk about longer strikes in certain sectors, such as oil refining.

On Feb. 11, the first protest held on a weekend, almost 1 million people turned out, mostly peacefully, across the country. Many brought their children so the young ones could, in the words of one demonstrator, “get a civic education.”

“Sixty-four is an age when you become more fragile physically,” far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon said on French television as he joined the protest in Marseille. “The purpose of life is not to work until 64. The purpose of life is to live.” Mélenchon is a healthy-looking 71 who, as far as I can tell, works full-time and enjoys it.

He’s in the minority. French retirees leave their jobs so young that they have decades of leisure ahead of them. Mostly voluntarily, but someone who’s laid off at 58 has very little chance of getting another job, even after Macron’s government loosened labor laws. That hypothetical person can benefit from up to three years of unemployment payments, but that doesn’t get them to 64.

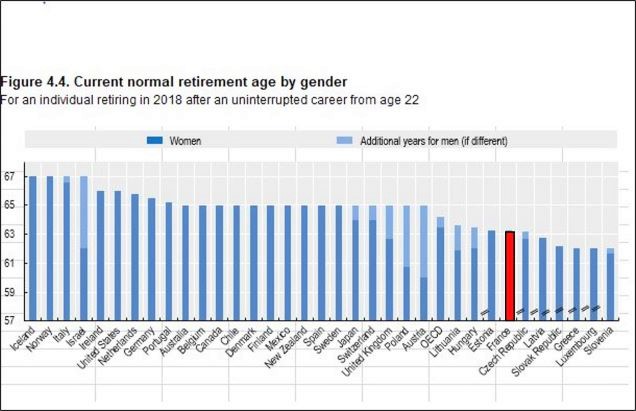

Source: OECD. Highlighting by Christine Swardson Olver

Extending the pension age hits hard here too because the government retirement system finances almost all of retiree revenue , and not very generously. The wealthy can accumulate assets and middle management can invest in company-supported supplemental programs. But there are no tax-advantaged savings plans like IRAs and 401(k)s accessible to a wide range of workers.

And as noted above, French workplaces can be extremely stressful places. Employee and manager suicides are a real issue here. I can’t say whether work stress is worse here than in the U.S., but I hear many stories from friends about top-down, clueless management and a total refusal to hear employee input.

Who wouldn’t want to retire as soon as possible under those circumstances? Especially in a culture that so values leisure time. And in a country where health care is guaranteed at any age, as long as you keep paying your taxes.

The government has done an astonishingly bad job of selling the change to the public beyond saying that the system, which could face a €10 billion deficit in coming years, needs shoring up.

“We haven’t made a case beyond the accounting case of why this reform is necessary,” said Benjamin Haddad, a deputy from Macron’s party. He was speaking at a breakfast for British and American reporters hosted by another deputy, Astrid Panosyan-Bouvet. (She happens to be the legislator for the part of Paris where I live; I wrote about her here.)

The measure passed the Assemblée Nationale, the lower house of parliament, last week after a chaotic 10 days of debate in which the center-right Républicains voted with Macron’s Renaissance party and the far-left and far-right proposed some 20,000 amendments (Most were eventually withdrawn.).

It now will be considered by the more measured Senate. If passed there, the two houses will have to agree on a compromise version, which should be interesting since the lower house ran out of time and never actually voted on the entire piece of legislation or even the change in the retirement date.

The idea seems to be that the public can be won over AFTER the measure is passed by parliament, or even, as Macron has vaguely threatened to do, enacted by decree. After that, said Deputy Christopher Weissberg, the government can turn to incentives for companies to retain and retrain older workers and in general try to reshape the work environment. He represents many of the French citizens living in the U.S. and Canada (what an excellent idea!)

The other night, I watched one of the movies I alluded to earlier. In “Deux Jours, Une Nuit,” (Two Days, One Night), a woman played by Marion Cotillard returns to her job at a solar-cell factory after a medical leave for depression – and finds that her colleagues have been presented with an incredibly cruel choice.

Source: IMDB

While she was out, management made them vote to either allow her to return and give up their annual bonus of €1,000, or let her be laid off and keep the bonus. She lost, she found out when she arrived at work on Friday.

A work friend persuades management to hold another vote on Monday, and Cotillard’s character spends the weekend visiting her fellow workers, all of whom are barely getting by in a industrial suburb in French-speaking Belgium.

In the end, she too must make a cruel choice. It’s a reminder that work can be ugly, and to respect anyone who wants to be done with it.

Movies:

The Adventures of Salavin 1964

Que les gros salaires lèvent le doigt ! 1982

Happiness Is in the Field 1995

The Closet 2001

The Axe 2005

Ils Ne Mouraient Pas Tous Mais Tous Etaient Frappés 2006

Two Days One Night 2014

The Measure of a Man 2015

At War 2018

The No-Job Agency 2016

Another World 2021

Between Two Worlds 2021

Full Time 2021

The Sitting Duck 2023

Feature Image: Change.org

Ann, you are right that the French are stressed out by work. And you know what? The highest level of stress and suicides actually are found among civil servants, who cannot be fired! It turns out that in such environments the lack of any realistic possibility to quit and get another job puts the employee in a terrible situation- possibly years of suffering. The French do not job hop, and this is why 58-year olds cannot get rehired. I very much after with you that this is an important aspect of the current strikes. I would like to see Melenchon enjoy his retirement, though.

Thanks David! I’m glad you enjoyed it. Very funny about Melenchon, I wonder if anyone has suggested it…..

Anne, as always I read your post and your perspective with pleasure and I enjoyed your analysis. You touched on another of the many French paradox. Their relationship with work (le travail)? They don’t want to work 2 more years but 77% of them/us according to l’Institut Montaigne are “satisfied” in their jobs today. Another contradiction is that even if they protest against the potential reform most of them are convinced that it will pass anyhow. Those who puzzle me the most are the “lycéens” and students who have not even started to work and who don’t want to work tow more years already. And I second the previous comment wishing for Mélénchon to retire…promptly.

Thanks, Jacques! Yes, the idea of a young person even thinking about retirement cracks me up. Although I suppose it’s also a general anti-government protest.

Great post, Anne! Would you say that “Le Bonheur est dans le pre” would fall into this category of film also? Thinking mostly of the striking workers.

Thanks and good call! I’ve updated the post and the list.

From an American perspective: get that decent retirement if you can. I was functionally aged out of the workplace by age 58. I hung on with freelance jobs and stacking quarters for the laundromat, and family help. Had I not picked my grandparents well, I’d be living out of a van right now.

Awful! In France people age out at 58 but between unemployment and early retirement they can at least hang on.