Most of my walking in cemeteries has been at Père Lachaise and Montparnasse, where the headstones and mausoleums honor people such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Edith Piaf.

But I’ve found a very unusual cemetery in my other home town. In this one, the graves are unmarked.

There are more than 3,000 of them. They are on the grounds of what used to be called the Western State Lunatic Asylum, in Staunton, Virginia. I’ve become fascinated with its shocking history and what it has become today.

Western State, founded in 1828, was one of dozens of architecturally magnificent institutions built in the United States to house psychiatric patients. Every state had at least one. According to this article, they held more than 500,000 patients by the 1950s.

There was one in the town where I grew up: Athens, Ohio. Like Western State, the campus includes multiple brick buildings on a green and inviting campus, and hills that we sledded down in winter. The idea was that patients would benefit from being outdoors in beautiful, inviting settings (more below on the tragic turn patient care took at these asylums). The building complex is now owned by Ohio University.

Western State went through several iterations as new medications and treatments reduced the need for institutionalization. The site was closed in 1976, then became a prison from 1981 to 2002. It stood abandoned for a few years before it was purchased by a developer. (A modern facility on the east side of town still serves patients.)

Today the old complex is home to a hotel and conference center,

Several condominium buildings

And a sports club.

But to me, that’s not the interesting part. Unlike many other such sites, Western State is only partly developed. You can walk freely on the grounds—without seeing a soul—and find many remnants of the old days. This building backs right up to the rear of the hotel.

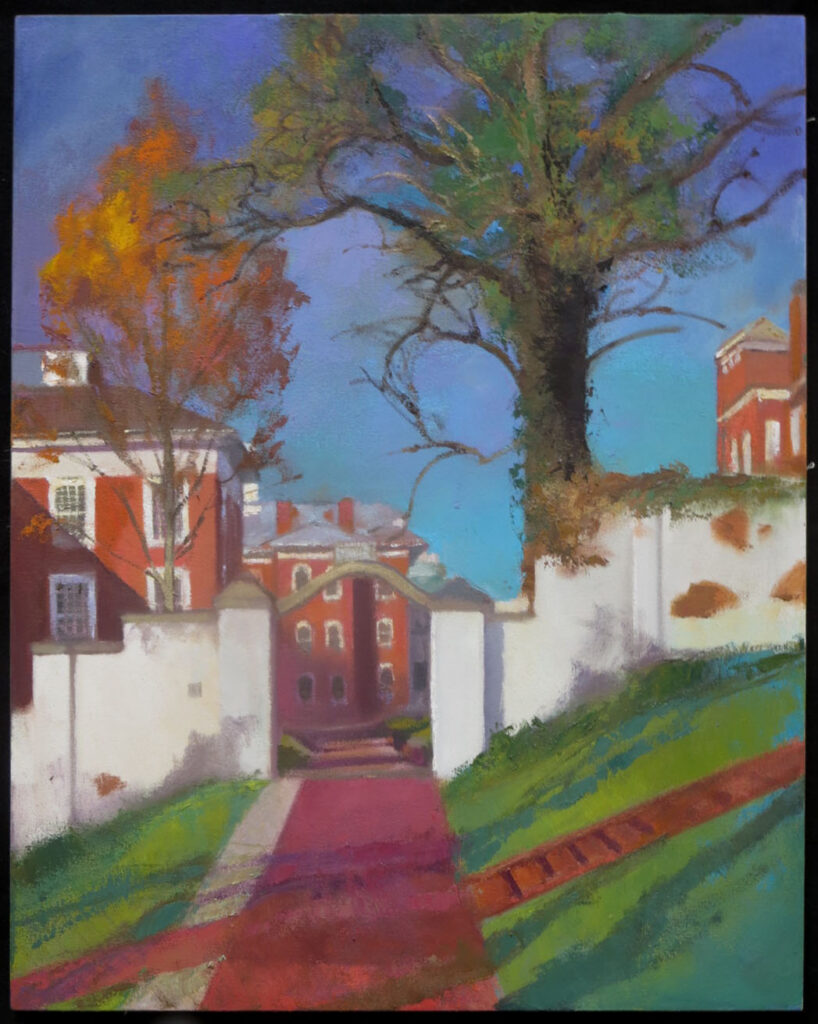

This striking arch was also the subject of a painting by our friend, artist Lincoln Perry.

Photo: Lincoln Perry

But the most troubling reminders of Western State’s past are just off-site.

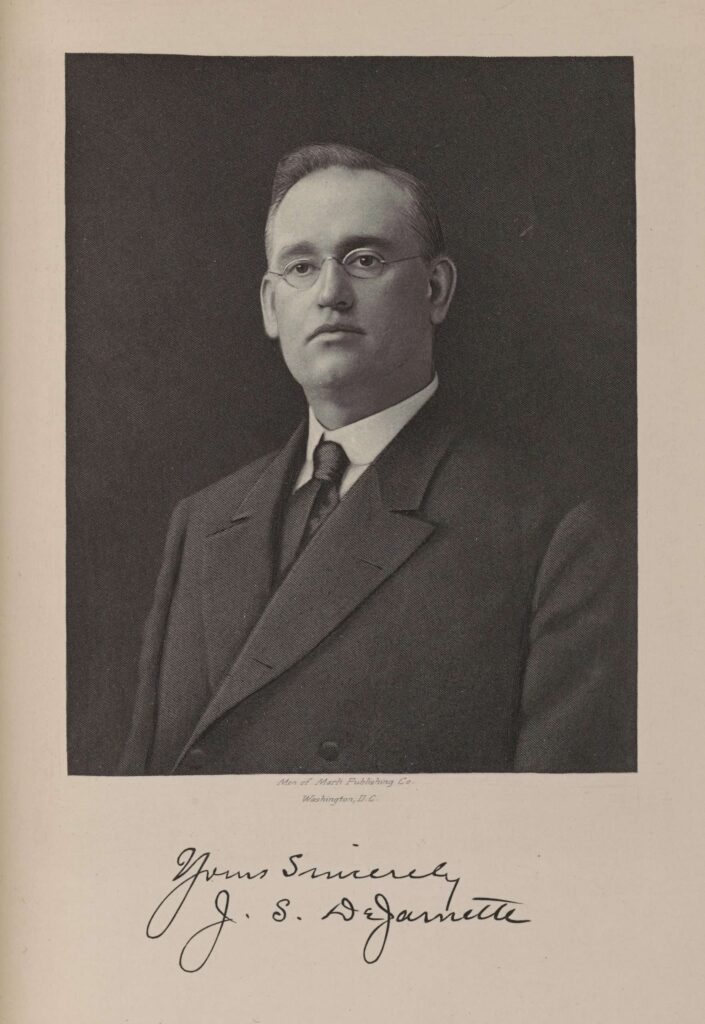

On the other side of the hill, less than a mile from this complex, is a symbol of the worst of mental health care. It goes back to 1905, when Dr. Joseph S. DeJarnette became Western State’s director. He seemed to be a proponent of the so-called moral treatment method, which calls for surrounding patients with natural air and light, as well as gentle treatment. At the same time, though, he was influential in persuading the Virginia legislature to pass a 1924 law authorizing forced sterilization of patients in mental institutions, and performed hundreds of the procedures at Western State. He even praised Germany’s eugenics program in 1934.

University of Virginia Special Collections

It’s almost impossible to imagine that more than 60,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized between 1907 and—incredibly—the mid-1970s. Virginia, which sterilized more patients than any state but California, didn’t repeal its law permitting sterilizations until 1974.

DeJarnette testified against a 1927 challenge to it before the U.S. Supreme Court, and the law was upheld. Carrie Buck, the 18-year-old allegedly “feebleminded” woman who had been sterilized, later turned out to have been raped rather than being promiscuous, as was claimed during the court case. Nor was she epileptic or “feebleminded,” as the suit claimed. When eventually released, she went on to live a normal life.

In 1932, the doctor founded the DeJarnette Sanitarium, for private patients, not far away. Even after he was pushed out of Western State in 1943, he continued to practice forced sterilizations at the sanitarium for another four years, as well as lobotomies and electroshock therapy.

The sanitarium buildings, universally known locally as the DeJarnettes, are abandoned today. The site is for sale and trespassing is forbidden. Friends who grew up here describe sneaking onto the property and seeing unhoused people sheltering there. Both complexes have horrible histories, but at least parts of the Western State Complex have been turned into something good. There is nothing good here.

The cemetery is on the far side of the complex, across from the former dairy. In theory it is fenced off, but no one polices it.

The reason the graves are mostly nameless is that families were ashamed to have loved ones in a mental institution. The stigma was strong then. The gravestones apparently had numbered codes on them originally, that could be matched with a registry, but the numbers wore off.

The dead sleep overlooking the buildings where, for some of them, a madman deprived them of the most basic human right: control over one’s body.

I enjoyed this, Ann. I have also visited the cemetery at the former Western State and have spent a few nights at the hotel on the property. You may be interested in the recent novel NIGHT WATCH by Jayne Anne Phillips (which won the Pulitzer for Fiction last year) set mostly in a “lunatic asylum” in West Virginia shortly after the Civil War. (I didn’t love the book, but the setting was interesting because of my familiarity with Western State and DeJarnette’s sanatorium.) Of sourse, I have also strolled through Parisian cemeteries, looking for familiar names.

Thanks so much, Clifford. In fact, reading Night Watch helped motivate me to write about Western State, something I have long wanted to do. Jayne Anne Phillips grew up very near the asylum the novel is based on, though it’s clear the story is fictional.

I lived in Staunton briefly as a child in the early 1950’s, and the memory of this place – although no one ever explained it to me, and I never visited it – still haunts me. Going down that long hill on Rt. 250 into town, the campus stood just on the left behind a tall fence. One day I saw a man peering sadly out between the bars of the fence. It was pouring rain but he seemed not to care, or even notice, and I could see water dripping off of him. It’s where “crazy people” went to live, it was explained to me.

My own mother briefly underwent outpatient treatment at a place she called “DeJarnettes,” but I never learned what went on there or even where it was. The graves at Western State remind me of the rows of “unknowns” in Arlington National Cemetery. At least the people buried there are honored for their sacrifices.

Thanks so much, Gary. What a chilling image you describe. Friends tell me the patients were sometimes allowed to wander around downtown as well, which can’t have been much fun for them or the local people.

Well done telling a story about a bad part of our country history that most of us forget or might not have known

Lets read more

CONGRATULATIONS 🎉

Thanks so much, Joe!

Anne, excellent post. It reminded me of this book of poetry, by the very talented daughter of an old friend who grew up in Virginia and was as shocked by a similar institution there, the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded. Here’s a link:

https://www.mollymccullybrown.com/colony

Merci, Lee! I’d never heard of that institution but I see that Carrie Buck, the subject of the test legal case, came from there.

Thanks for sharing this important and disturbing piece of history. In high school I volunteered at a similar state institution in Worcester, MA and saw such despair and neglect.

Thanks, Ellen. By that time those institutions were extremely overcrowded, too.

Hi Anne, Great piece and thank you for writing about it. My mother was in and out of the Norristown State Mental Hospital in Norristown, PA. I used to have to go spend the weekend with her when I was 11 and 12; so many memories came back. In 1965, they treated her with LSD! Not a set of memories I revisit often, or ever. Thank you for this.

Thank you, Barbara! That must have been difficult. I don’t know why you have acquired a secret identity, I’ll see if I can change it.

DeJarnette also performed lobotomies and electroshock therapy. Which was therapeutically normal back then… but people who had relatives there will tell you the place is haunted

Thanks for the reminder! I’ll update with those other horrrors.

So poignant and sadly, it reminded me of how our government is “erasing” the names of so many from our historical markers and records.

Good point!

Good photo essay on a difficult subject. No experience with such institutions, although several of my Marietta College friends worked in Ohio hospitals as alternative service during the Vietnam era. I have had experience however with former inmates in the aftermath of O’Connor v. Donaldson in 1975. That case resulted in a ruling that involuntary confinement required due process and a showing that the potential ward was suffering from a cognizable mental illness (enter the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and were a danger to themselves and others. Later in 1979 the standard of proof was raised to “clear and convincing”. This resulted in simply releasing many people who then moved onto the streets. There was inadequate funding for their care, a shortage of half way houses, and it led to many people facing deprivation and hardship. I worked with a few. In tatters and rags…not a one wanted to go back to Spencer State.

I remember that period. Deinstitutionalization may have been a good idea in theory but not after it turned out there was no plan for those poor people.

Thanks Anne. I read a book about Carrie Buck: Imbeciles, the Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and Carrie Buck. What so shocked me was the fact that so many prominent, “learned”, Americans supported sterilization.