At least Le Rubis was unchanged.

My favorite bistro when I was a student in Paris looks just like it did back then, even though the neighborhood around it north of the rue de Rivoli has become much more chic. I spent many happy, and tipsy, hours there. More on my drinking companion later.

My visit was part of a nostalgia tour I made around the city to celebrate the 50th anniversary of my college junior year in Paris. I started with the places where I’d lived. As I walked along the Boulevard Saint-German, where I was housed during the fall semester, I reflected on a truism I’d heard: Your first Paris neighborhoods are the ones you’ll always remember. Even if they bear little resemblance to your memories.

The building was just a few doors from the boulevard’s eastern end. My roommate and I were in a bedroom on the downstairs floor of an apartment owned by a doctor and his wife.

They had little idea of what college students required. Breakfast, for instance, was in a closet-sized room off our bedroom. We were supplied with a water boiler for instant coffee and a plastic package of biscottest, on which we spread oversoft butter, to eat. No fridge, no sign of our hosts.

This deprivation proved disastrous in winter, when we had to keep our pots of yogurt out on the window balcony to stay cool. I knocked one overboard one night and heard a scream of anger from below. It had landed on a lady wearing a fur coat and, yes, I had to pay for the cleaning.

We were allowed upstairs once a week to bathe, by appointment. And, as per the rules of our program, we dined with the couple once a week. Since my roommate spoke very little French, it was awkward.

It didn’t help that she was the one with all the demands: Softer pillows, more covers, more frequent bathing. All transmitted through me. I tended to follow my father’s adage: “Adventure is misfortune, properly construed.” But to our hosts, I was the bad guy.

Still, it was fun in the present day to see how the quartier had changed. The boucherie chevaline (horsemeat butcher) had been replaced by a wine store chain, next to an eyeglasses chain, for instance.

Velibs, of course, weren’t around in 1974.

Strolling around the neighborhood, I was astonished to see how close I had lived to a lovely 17th-century church, itself near the medieval Collège des Bernadins, an architectural marvel. Was I even paying attention to my surroundings back then? Too much pouting about rancid butter, too little walking in the neighborhood?

Our relations with the couple deteriorated sharply when my roommate got into a screaming fight over who got to use the one phone line: Our doctor-host, for a patient call, or her, to talk to her boyfriend in the U.S. It was near the end of the semester. At the break, she left for home and I departed for other quarters.

I came to Paris with what was then called the Institute of European Studies, now named IES. It accepted students from a variety of colleges and universities – incredibly, Cornell, where I went, didn’t have a Paris program back then. Students could take classes at various schools around town if their French was good enough or at the IES center on rue Daguerre in the 14th if needed.

I spent a lot of time sitting in shabby cafés on that street, drinking coffee, eating CaramBars and feeling very un-French. I felt removed from the other students in the program and from the French students I happened across. That café is spiffier now, but the memories remain.

It didn’t help that this life was almost totally devoid of males. There were 70 girls and four boys in the program, and young French men, to the extent I managed to meet any, were uninterested. Algerians, recently arrived in France, often approached me on the street and said they wanted to chat. But it quickly became apparent that talking was not their primary goal.

I took two classes at Sciences Po, then and now a prestigious political-science school on the rue Saint-Guillaume in the 7th arrondissement.

They were interesting, but what I mostly remember is going to the school store at the end of the year and asking how much a T-shirt was.

“Ten francs,” said the student manning the counter. “Wait, are you American?” Yes. “For you, 17 francs.” He was joking, but it wasn’t funny.

My spring semester housing was a lot more pleasant. I moved into the apartment of a widow, her two sons and a maid; two other IES students were resident. We got to use the actual kitchen for breakfast, spreading fresh butter on our fresh bread, and our weekly dinners were filled with interesting conversations.

We became friends with the son and were invited to spend weekends at the family country house: basically one room atop another about 90 minutes southwest of Paris. That man is still my friend.

The family apartment was on the Avenue Victor Hugo near the Etoile. I remember the neighborhood as being extremely posh – I mean, there was a Le Nôtre bakery next door. My return visit showed a street flush with high-end chain stores and no fancy bakery. Is that more or less posh?

The food was better than at the cafeteria in the 7th, too. What my parents and I hadn’t realized when we signed up for the program was that the money they paid for my daily dinner covered only the cost of a student restaurant, that is, a huge subsidized cafeteria in a bleak university building, of which Paris had many. At Victor-Hugo, we ate at Université Paris-Dauphine, where the meat was actually chewable and something resembling salad was served.

Some students just ate at restaurants every night. My budget didn’t permit that.

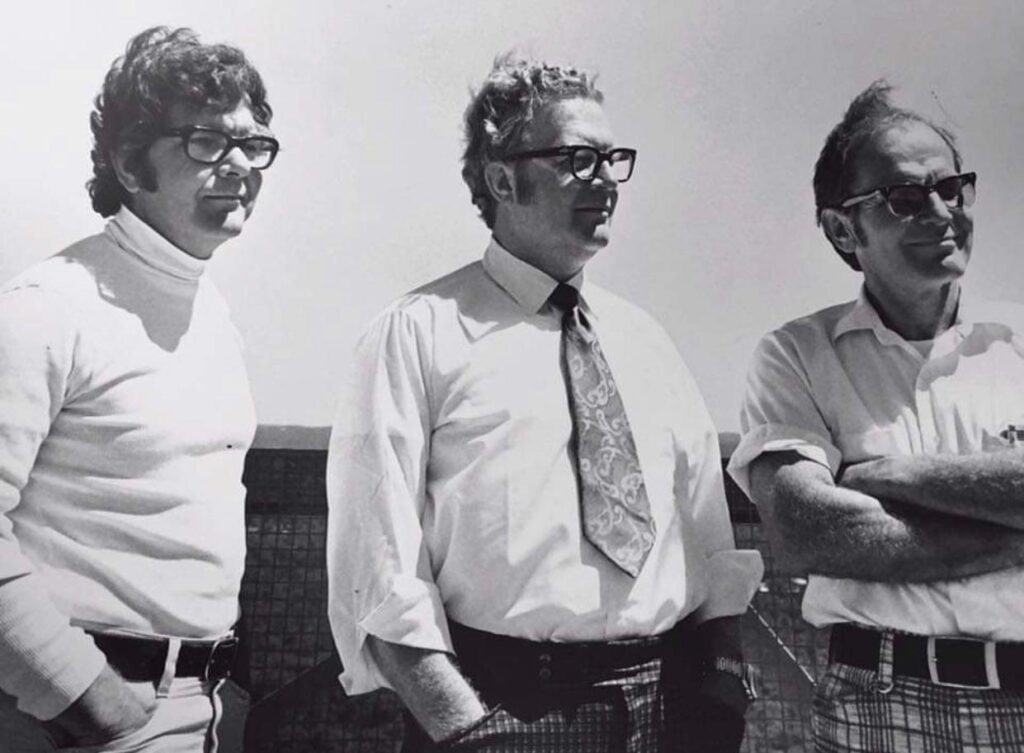

Every once in a while, I got treated to dinner and drinks, though. This was when Uncle Don came to town. My father’s brother lived and worked in Milan at the time. His family had returned to the U.S. and he was going to join them in the summer. In the meantime, his job occasionally brought him to Paris and his love of good food and drink took him, and me, to Le Rubis (yes, it means The Ruby).

In the evenings, it was hopping, as it was not when I stopped by on a rainy midafternoon recently. In addition to the wide-ranging wine selection,

waiters would serve plate after plate of crusty bread spread with cheese, or charcuterie, in both cases also with butter.

Then we’d stagger off to eat, usually with other colleagues of Don’s in tow. We almost always went to a nearby restaurant whose name I don’t recall. Don referred to it as the Ugly Sisters because it was run by two cranky ladies (what can I say? It was a different time.)

It seems to have become a gallery.

Two mysteries emerge from this walk down memory boulevard: One, why did I do so little exploring in this beautiful city? I went to museums and visited churches, yes. But I don’t remember taking long walks through quaint or funky neighborhoods the way I do now. Did I ever stroll down the historic rue Mouffetard near my first apartment, or wander around the ponds of the Bois de Boulogne from my second? Not that I recall.

Second, what was it about Paris that made me fight so hard to return? Two years later, at the end of an internship here, I visited every English-language media bureau in the city to see if I could get a job that would allow me to stay on. They all turned me down, but 20 years later I arrived as a foreign correspondent and never left. If I ever got into a pout on my return trips, I don’t recall.

In the end, I think that despite gentrification and modernization, Paris never really changed. I did.

Note: No photos seem to have survived Don’s and my escapades in Paris. Here’s one of the three brothers from around that time: Roger, the youngest, on the left, then Don, then my father, the oldest.

Photo courtesy of Sue Wadlow

Your piece brought back so many memories of my 14 months in Paris in the late ‘70s. I had finished college (Vanderbilt) and was living hand-to-mouth in a tiny maid’s room overlooking Place St. Sulpice. No papers, no visa, nothing. I, too, wonder why I didn’t do more exploring. I remember spending my time looking for cash-paying, under-the-table gigs: dog-walking, house-sitting, typing French-to-English translations, buying lunch for Vogue editors shooting the collections. Still, it was all pretty glorious!

Thanks! I suspect, justement, that having no money dampens one’s enthusiasm for random exploration.

What a fascinating window into your early years in Paris, Anne! I could sense the real-time feelings of navigating some challenging sitituations. I guess it was the fact that you ‘survived’ that made you want to come back!

Well that’s a good explanation, thanks!

memories

What are the odds, I was an IES student for a year in 2008. All worlds collide in Paris!

They sure do, and thanks!

Really lovely. It helps pry open the door for all of us to revisit our own “first” stays: A summer with a family living a few blocks from the Pantheon, the apparently standard one-shower-a-week, ditto for the joining the family for meals…and that inexplicable lack of exploring. But we would later compensate for that.

Yes, maybe in our youth we explore ourselves, not our surroundings. Thanks for the kind words!

My memories of Paris don’t go back as far back as yours, but my wife’s do. Thanks for this elegant walk down memory lane.

You are so welcome, and thanks!

So many memories like yours–was in Paris between sophomore and junior years in college.

Thanks, Shep!

Nicely done and love the photography. I was also a student with IES but in Vienna, which had echos of The Third Man still in 1969. My roommate, now retired lawyer in Cincinnati, and I shared a large, high ceiling room in the flat of Herr und Frau Kahler in the distinctly unfashionable zweiten bezirk across the Donau Kanal from the RingStrasse and the Palais Kinsky where the school met. Our gender situation was somehting of a mirror of yours…180 girls and maybe 80 boys. The cultural experience was …profound. I have returned only once, with Sue, but only briefly. Your comparisons with the past are interesting, although as you note not unexpected. And if indeed the life of students and artists is doomed to a certain chicness of poverty, I share your recollection. A lump of lignite coal in a ceramic corner stove (green thank you in color but not in environmental terms) was our salvation in the brutal cold and grey of Vienna in February. We then faced a half hour walk to the Kinsky dodging dog waste and mounds of yellow snow. I recall Paris’s plague of dog by products in a city that simply adores les chiens. And smoking! The French curse was Gauloise and the Austrian Tabak was just as bad. Ocassionally one could find Players Navy Cut, better and with a cool looking sailor on the box. The Prussian military did not invent the use of the bayonet, the Vienna hausfrau did as a way of gaining entry onto the Strassenbahn. More ominous was the Odyssean journey home from classes which put us between Leupold’s with its fine krugel bier on one side of the street and the Melkerstifts Keller with its rot and weiss wine on the other. Some of our cohort did indeed fall to those sirens. Still, as you so ably report, time and the vagaries of memory, smooth the rough edges of what we recall. It was after all not just a classroom learning experience. It was, for most of us I’d guess, a romantic adventure, a one off, a place not really home but to which one cannot go again. And of course being young, we never thought about how that magic time might come to an end, and those nooks and crannies that no doubt held all manner of cultural and historic treasures, would recede from our grasp and even our touch. And being poor didn’t help.

Thank you for these wonderful memories!

Thanks, Anne. That was a great piece about your revisiting the Paris of your past. There really were more snarky attitudes to contend with back then, although the South of France was far friendlier.

Nice memories. We didn’t have junior years abroad and the like when I was in college. Not sure I would have appreciated places like Paris as much as when I was older.