“Every sensible and rigorous theory of language shows that a perfect translation is an impossible dream. In spite of this, people translate.” – Umberto Eco, “Experiences in Translation”

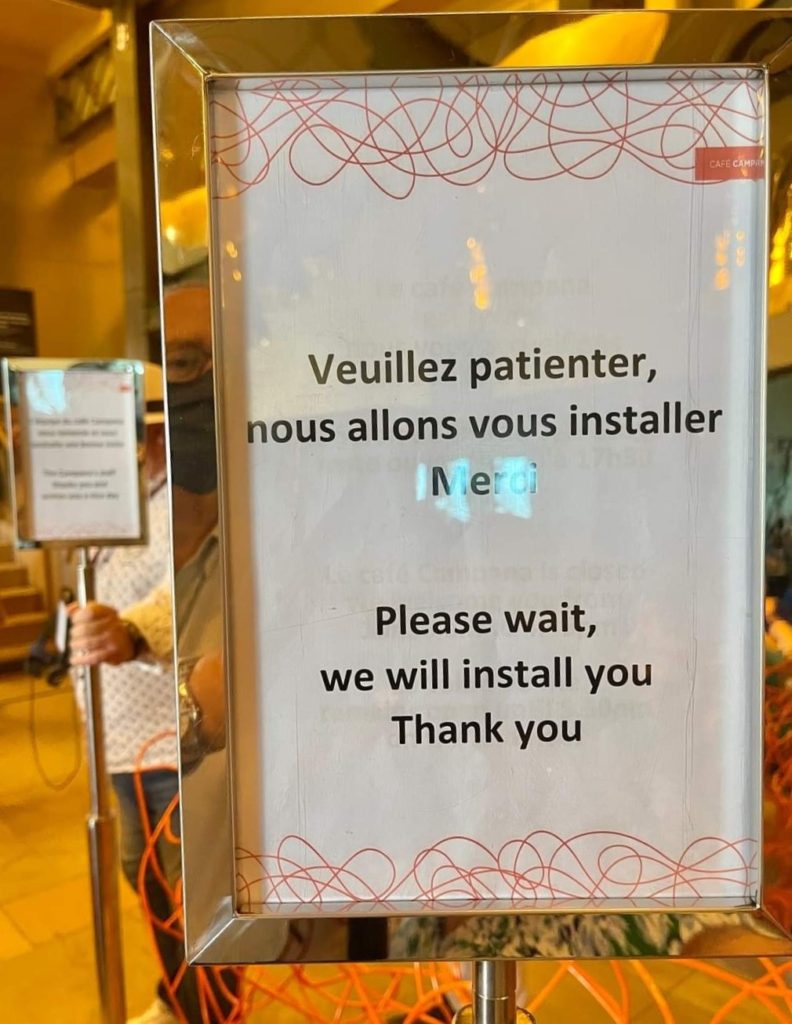

Now, they tell us, AI will take over translation from people. Tourists in Paris can say “Where is the Louvre?” into their phones, push a button and show the screen to a native, who will read “Où se trouve le Louvre?”

This is fine for simple needs. But one doesn’t just translate a language. One translates a culture, a history, a way of thinking. That’s both subtle and complicated. People better qualified than me, such as John McWhorter here, say the same.

French is a compilation of what it means to be French, of the experience of being French, not a bunch of words typed on a keyboard. Artificial intelligence never attended French kindergarten and saw the teacher tear up their drawing because it was ugly. It never learned to say “Bonjour” when walking into the bakery. It never had to pass the baccalaureate or go to mandatory lunch with Mamie (Grandma) every Sunday. It never demonstrated against cutting social benefits or went on vacation five times a year.

It’s no wonder that many French phrases sound vague, contradictory and untranslatable to language learners.

My favorite is “assumer ses responsabilités.” We all get what it means to assume one’s responsibilities: Do your job, take on the task, pick up the shovel. But native speakers of English would never say that in the way native French speakers do. We’d just say the actual thing: President Biden needs to persuade Congress to pass the infrastructure bill. Charlie needs to take the trash out. I need to play fewer games on my iPad.

Yet when I asked ChatGPT to translate this sentence (from the Le Robert definition of the phrase):

“Le patronat est quant à lui appelé à assumer ses responsabilités en terme(sic) de hausses des salaires et à mieux répartir la richesse produite par les entreprises.”

I got this:

“The employers are, in turn, called upon to take on their responsibilities in terms of salary increases and to better distribute the wealth produced by the companies.”

Wouldn’t English speakers be more likely to say:

“Bosses need to raise wages and give workers more of the profits.”

?

I asked my French-speaking friends on Facebook to suggest hard-to translate French phrases and got back a wonderful cornucopia of examples.

“Terroir.” We would say it means territory or land or place, but in France it means the complete natural environment in which a particular food or wine is produced, including the nature of the soil, the climate, altitude, topography and more. – Timothy Boggs

Another example of cultural context: laïcité. This term technically means secularism, the separation of church and state in France. Dating from the late 19th century, it was a way to get the Catholic Church out of government affairs. But the idea has been bent in recent decades to justify, for instance, banning Muslim headscarves in government buildings, restricting home schooling or –- I am not making this up -– prohibiting “burqinis” from public swimming pools.

Think of all the things you have to know about France to understand that discussion. The Economist does a good job of explaining here.

“Jolie-laide.” Unconventionally attractive – Gabrielle Glaser

Another equally broad term: “social.” This does not refer to the upcoming cocktail party. It’s an umbrella term for France’s enormous package of welfare, labor and health benefits. (Thanks to Julie Sullivan for the link). Chat GPT did get that right, I admit.

I was once at a press briefing where a European Union official was explaining economic reforms that would inject more capitalism into the European economy. Reporters of different nationalities all had questions about how it would work. Then the French reporter raised her hand: “Et le social?” That was all she had to ask to make clear she wanted to know if people would lose their jobs or benefits.

“Être solidaire” Yes, we have the concept of solidarity, but it’s a whole social philosophy in France that’s hard to translate! — Hope Newhouse

President Emmanuel Macron in 2022 befuddled English-language reporters when he said of people who hadn’t gotten vaccinated against COVID that “les non-vaccinés, j’ai très envie de les emmerder.”

Emmerder comes from merde, whose meaning I presume everyone knows. But Macron wasn’t saying anything scatological about the unvaccinated. Depending on how the word is translated, it could have meant anything from “piss them off” to “irritate them.”

Reporters from American and British publications generally went with the former. I might have said “get in their faces,” which, like piss-off, conveys that Macron was trying to sound like a tough guy rather than his usual mode of pedantic college professor.

ChatGPT actually did a nice job with this one: “I really feel like annoying the unvaccinated ones.”

“Normalement” in the sense of Normalement, I’ll pay you back the money I owe you… (except maybe this time) – James Wilson

Longtime anglophone residents of France – I call us transplants — sometimes get around the translation/culture problem by adopting the French word, speaking in Frenglish. So my friend and France expert, Francie Seder, might say “J’ai un empêchement” – I have a hindrance — when she can’t make it to an event, while an American in the U.S. would be more likely to explain why, like, the babysitter is sick.

Similarly, we propose that we “faire le point” when we mean “Let’s review the situation.” (And we leave to “faire le pont” when we, along with everyone else in France, take a long holiday weekend.)

For the younger set: doudou. This convenient word means the object to which your child is inextricably attached, be it Teddy bear, dolly or blannie. As in, “We had to go back home because we’d forgotten the doudou and Pierre-Henri can’t live without it.”

It turns out that the field of untranslatability has attracted academic attention. Most notable is Dictionary of Untranslatables, edited by French philosopher Barbara Cassin. The publisher’s description says it includes “400 important philosophical, literary, and political terms and concepts that defy easy—or any—translation from one language and culture to another.” The words come from more than a dozen languages and there are more than 150 contributors.

I was unwilling to shell out $75 to buy the book but via Amazon’s Look Inside I can tell you that the first sentence of the first definition – the word is “abstraction” – is 59 words long.

The book has been translated into at least seven languages.

“C’est hallucinant!” Amazing, out of this world, crazy, incredible, astonishing….but all with a certain soupçon of irony – Ladka Bauerova

“France is a paradise inhabited by people who believe they’re in hell,” wrote Sylvain Tesson, and the language reflects that negativity. So, in these examples supplied by Anne Bagamery, “C’est pas évident (it’s hard), or il fait pas chaud (it’s cold), or ce n’est pas bête (that’s smart) – any French expression that uses the negative to convey a positive.”

Of course, there is c’est terrible and c’est pas terrible, both of which can mean the opposite of what it written, but not always. I don’t even try to get that one right. I remind myself that in English, we have bound, bolt, buckle, fast, left, oversight, sanction and many other words that are their own opposites. This video from comedian Gad Elmaleh illustrates some ways in which English, too, can be very vague.

“Système D” As I understand the term, it means more than just, say, “workaround”, because it is often used in the context of navigating a fonctionnaire (bureaucratic) culture. — Andrew John

My friend Alice Kaplan, a very distinguished France scholar at Yale University who also writes about and teaches translation, turned to a translator when her novel, Maison Atlas, was to be published in French.

Why, I asked, given that you are totally fluent in the language? She explained that she had worked line-by-line with the translator, Patrick Hersant, on the details of the text. But, she said, there was no question of doing it herself:

“I don’t have the music in French that I have in English, and when I read Patrick Hersant’s translation of my prose, I really do feel that it has come home to France.”

If we get to the point where artificial intelligence can do a translation like that, we have a lot more to worry about than languages.

In the meantime, bonne continuation, whatever that means.

Bien joué!

Formidable!