I’ll come out and say it: Voter ID is a good thing.

That’s a controversial view in the U.S. But I have seen it work here, not once but for every one of the 10 times I have voted in France.

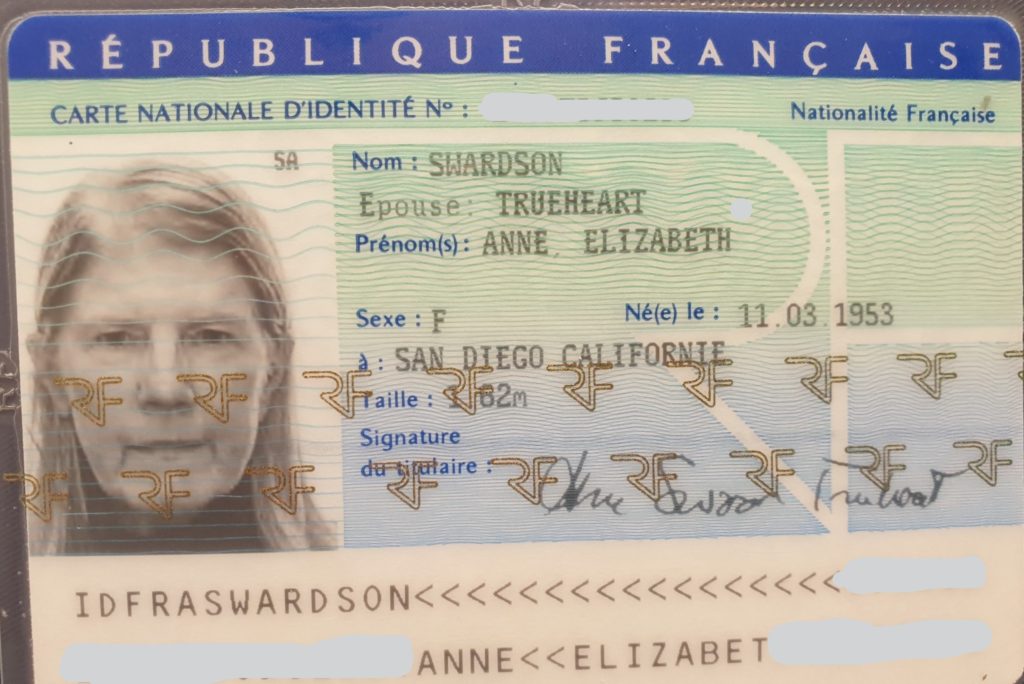

All voters carry their national identification card (a passport will do too) when casting a ballot, as Charlie and I did twice this month. The card also can be used any time you need a pièce d’identité, like boarding a plane to travel within Europe, or picking up a package at the post office, or making a withdrawal at the bank. Practically the only thing you can’t use it for is driving a car or accessing France’s national health system.

(There’s a reason why I, and everyone else, look grim in these photos. You’re not allowed to smile.)

Once you have obtained the card, which most people do at the age of 18, you sign up for the voting rolls online. A uniform, accessible ID gives me, and my fellow citizens, confidence that our voices are being heard and the election is fair.

Why does this system work so well? Because the government WANTS you to have that national ID. Even as recently naturalized français in 2009, we easily got one. You just have to show the right paperwork when you apply. The French cards are also easy to replace, which I, embarrassingly, have already had to do three times due to loss and theft. (It should be noted that French citizens born abroad have a much harder time getting and renewing cards.)

Unlike in the U.S., there are no closed government offices, no restrictions on sending documents in by mail or email, no arbitrary or politically set rules. The process is the same across the country, as opposed to the 51 jurisdictions of the U.S that oversee obtaining a driver’s license, many with different and difficult requirements. The only political disagreement over who can vote in France concerns whether to allow mail-in ballots.

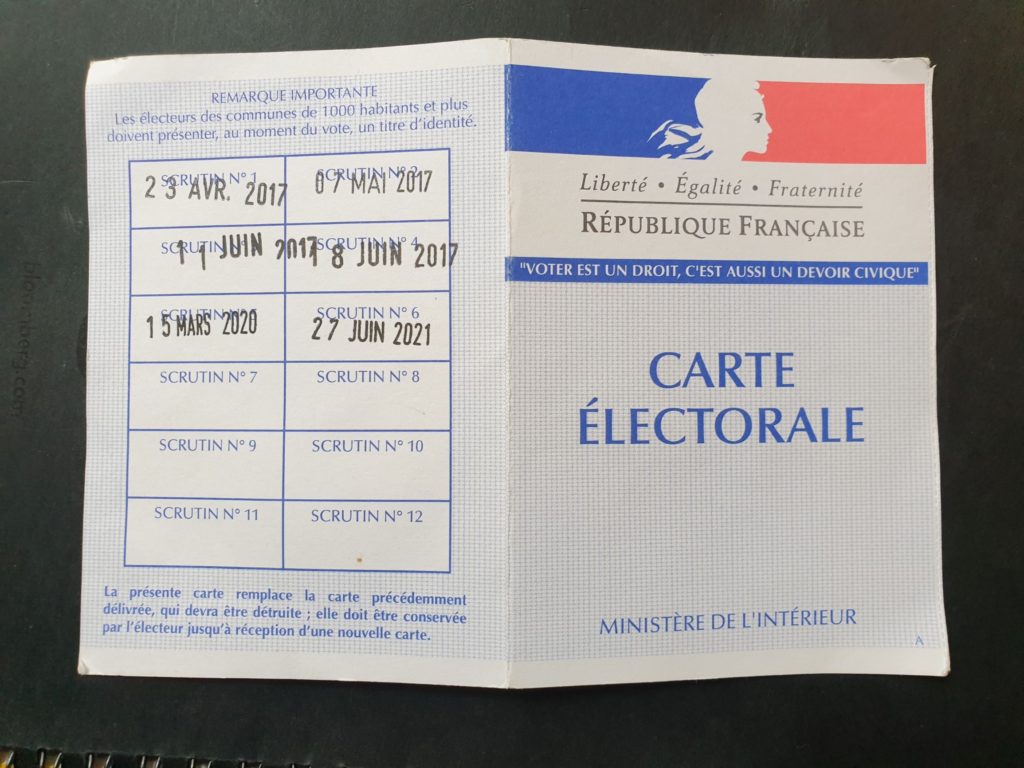

If you choose while at the polls, you can also show your voter card, and get a stamp proving what a good citizen you are. But it’s not a proof of ID.

If you choose while at the polls, you can also show your voter card, and get a stamp proving what a good citizen you are. But it’s not a proof of ID.

Charlie and I were voting in elections for the control of France’s 18 regions. The regions do have some power over a few issues, like transport, but mostly they serve to bolster the national ambitions of regional politicians. And they are a measure of the strength of France’s political parties a year ahead of presidential elections (more on that later).

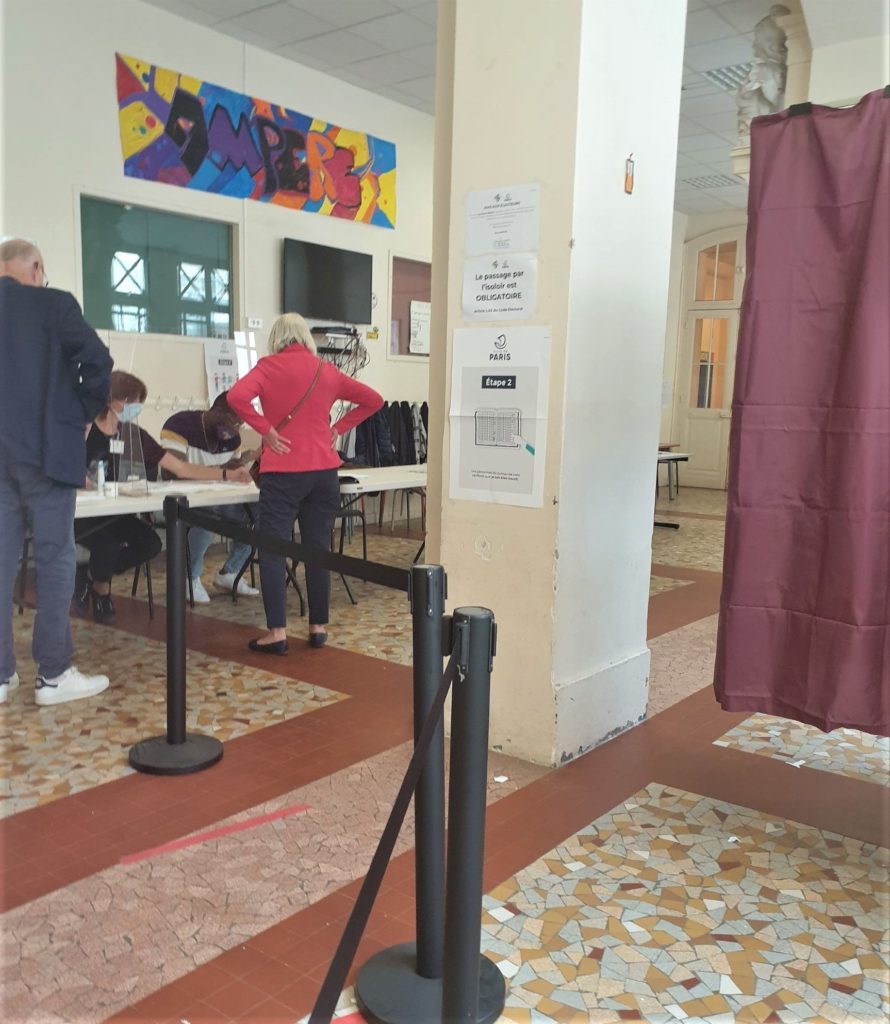

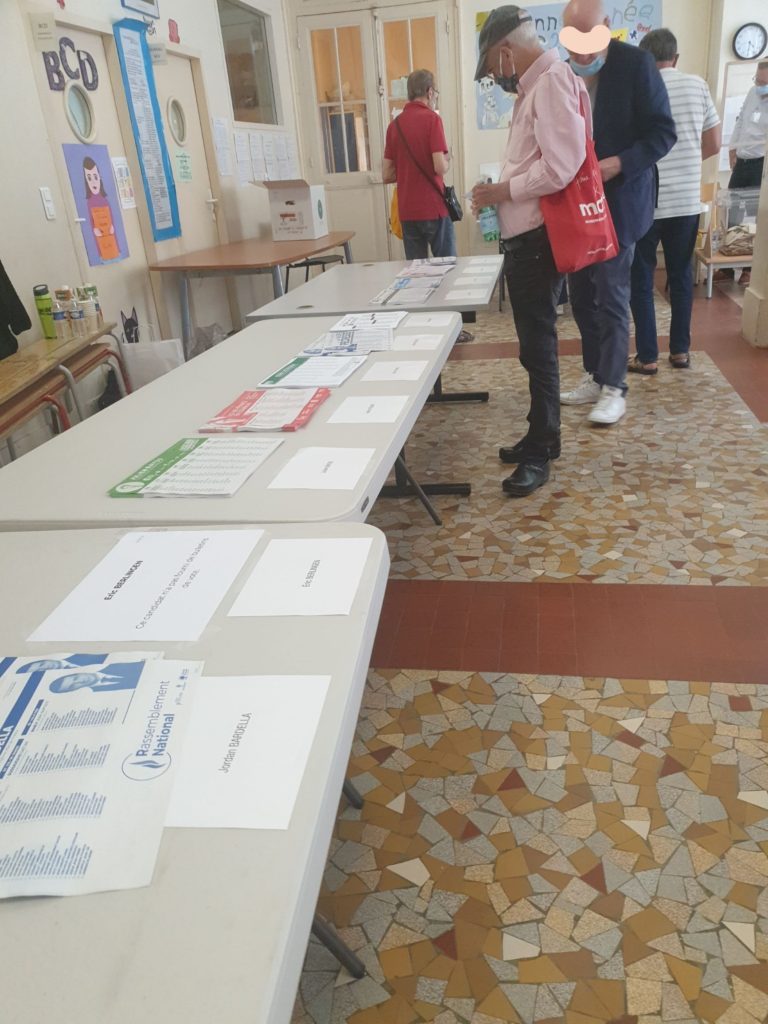

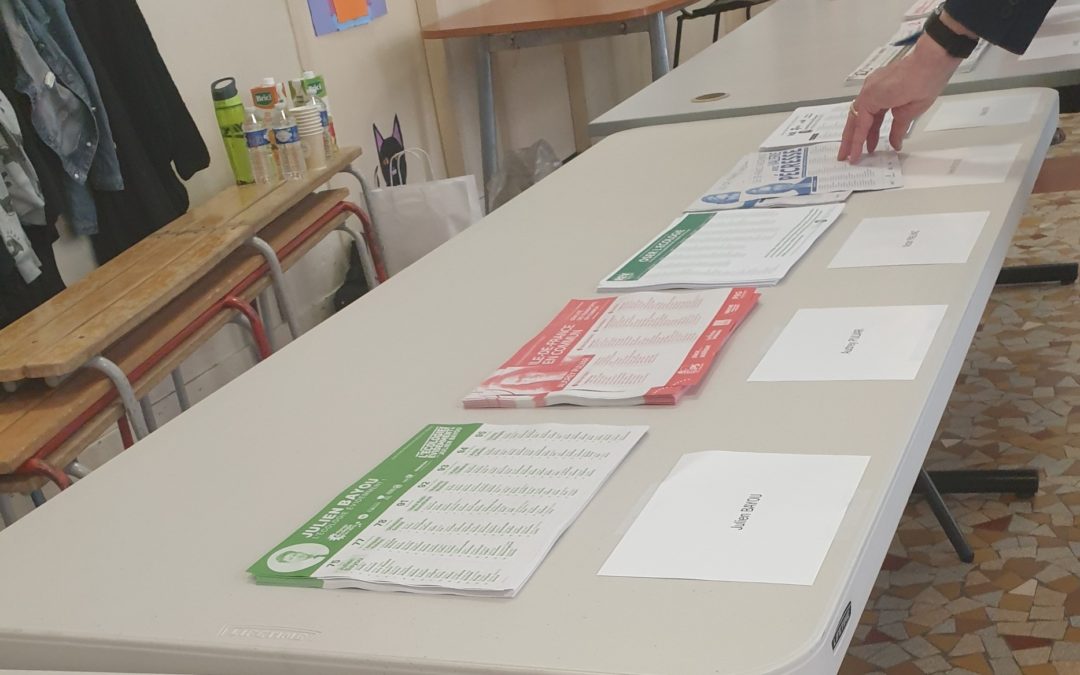

After check-in, we moved to a table that displayed paper ballots for each party or coalition running. Each included the name of the leader and all the candidates. (We had received similar documents at home by mail. Aside from street posters that’s the only advertising allowed.)

After check-in, we moved to a table that displayed paper ballots for each party or coalition running. Each included the name of the leader and all the candidates. (We had received similar documents at home by mail. Aside from street posters that’s the only advertising allowed.)

The piles shown here are for the first round of voting, on June 20. The number of parties was winnowed to four for the second round, on June 27.

Each time, to protect voting privacy, we picked up multiple ballots and then entered a curtained booth, where we inserted our chosen ballot into a small envelope. We discarded the unused ballots, imagining the waste of paper across the country.

Then we took our envelopes to a second check-in place, where we showed our ID cards again, signed a register and dropped them into a big Plexiglas bin. The person receiving it calls out “a voté” — has voted. It’s very satisfying.

This is the Holy of Holies, so photography was difficult.

After the polls close, volunteers – who says France is a country of bureaucrats? — tally the results and report them to the authorities. I participated in this the first time we voted, in 2012, and was struck by the care and seriousness the teams brought to the task. They were seeking to recruit counters this year too, but I passed.

The scariest prediction for this election didn’t come to pass. Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Rally failed to capture a single region. As expected, the party of President Emmanuel Macron, created only in 2016, busted out too. The center-right did well. Turnout, at 33%, was terrible, especially by France’s historically high standards.

It’s hard to know what all that means for the presidential elections next spring. All I can say is that when we exited the public school where we had cast our ballots, we felt good about having been heard.

Most persuasive. That this piece should go viral in my country.

Thank you so much, and here’s the link! https://anneswardson.com/my-country-believes-in-voter-id/

Great article! May. I share it? See you in December 👍😊🙏🏻

Please and thank you! Here’s the link. https://anneswardson.com/my-country-believes-in-voter-id/

I totally agree. In Switzerland, it is similar. But there there’s never been a problem with mail ballots.

In the US there’s always been this inexplicable aversion to a national ID card, which I’ve always found odd.