Thomas Jefferson is teaching me about French bureaucracy.

In a few days I will attempt to fly back to France from the U.S. When I left, I had every expectation of an easy return, immigration-wise, even during this time of pandemic border restrictions. French citizens, including me, and permanent residents are allowed in. (Other Americans are still prohibited, not just from entering France but from the rest of the European Union.)

But during our absence the French government issued an additional rule. Anyone flying from the U.S. — as well as from such other COVID-19 miscreants as Bahrain and Panama — must show up at the departure airport armed with a negative result from a test performed within the previous 72 hours. This in a country where labs can take as long as two weeks to complete their analysis.

How and whether this rule is fully enforced may determine whether I’m allowed onto the plane, if I can’t get the report back in time. (Charlie, who is scheduled to fly back two weeks after me, calls me his guinea pig.)

Bureaucracy is something that all of us living in France, whether native-born, naturalized, long-term resident or just off the boat, must deal with constantly. How do I replace a lost ID card? Will the authorities throw me out if I stay longer than the permissible 90 days? How do I renew my visa?

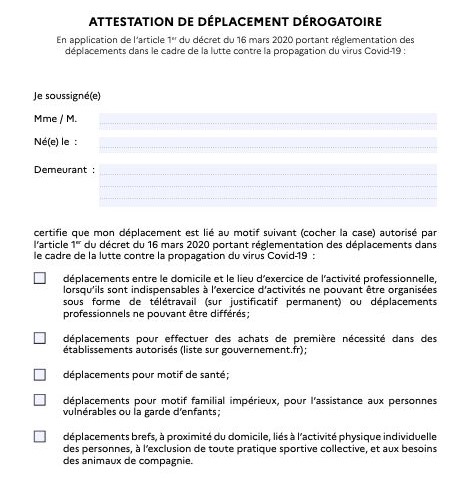

To make it even trickier, some rules are enforced strictly and others are not. Native French people have a clear sense of that. You can speed on the highway — if you get the app that shows where the radar stations are and slow down there. Smoking in restaurants, on the other hand, is never allowed, at least not since 2007. During the 56-day COVID-19 lockdown last spring, everyone had to carry a form justifying their absence from home and the cops were all over it.

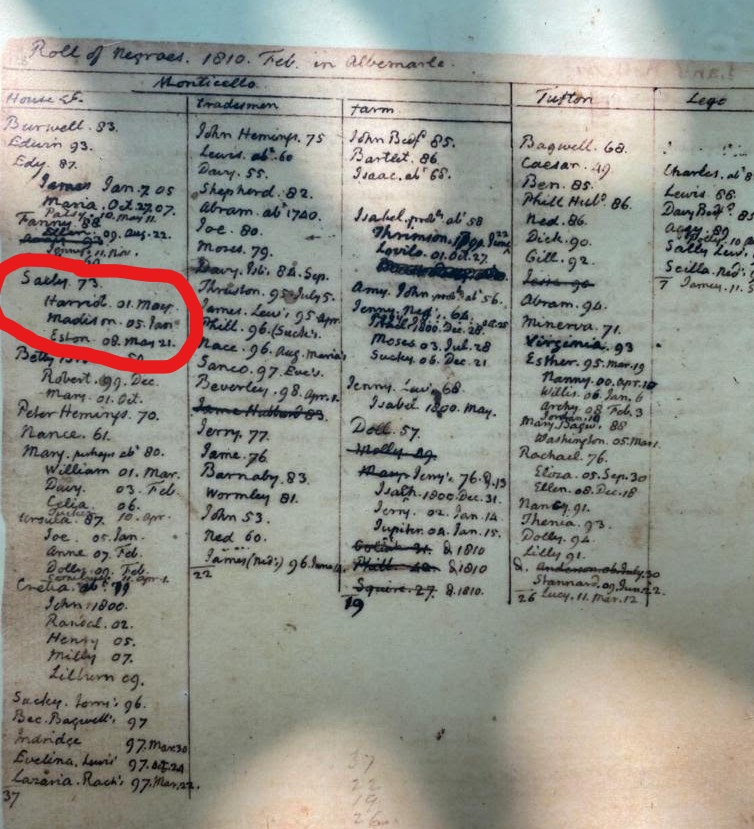

What does this have to do with Jefferson? As is well-known, when he arrived in France as U.S. Minister in 1784, he brought with him his enslaved 19-year-old valet, James Hemings. James was later joined by his younger sister, Sally, also enslaved by Jefferson.

France at the time practiced something called Privilège de la Terre, or Free Soil. Any enslaved person brought into the country had the right to request his or her liberty. If the enslaver denied it, the person had the right to request freedom from the courts. The court with jurisdiction over Paris granted every single application for freedom that came to it in the eighteenth century, almost 200 of them.

But first, entering enslaved and free Black persons were required to be registered, either on their own or by their enslaver. Jefferson did not do this. As Annette Gordon-Reed explains in her Pulitzer-Prize-winning “The Hemingses of Monticello,” he believed that the court under whose jurisdiction he lived “would not uphold his property interest in the enslaved brother and sister if they decided to challenge him.” The author of the Declaration of Independence and the representative of our fledgling democracy in France felt that registering the two Hemingses “would have put his status as a slave owner front and center for no good reason.”

Jefferson’s odious act of omission paid off, for him. The administration never noticed. Nor did James or Sally Hemings seek to stay in France (admittedly, a dangerous place at the time with revolution brewing), though they discussed it, Gordon-Reed writes.

Instead, Sally Hemings, who was bearing her first child with Jefferson when time came to leave France, used her ability to stay to get Jefferson to agree to emancipate any future children of theirs. James was freed in 1794, two years after returning from France. Sally (Sarah was her full name) was tacitly freed in 1826 after Jefferson’s death, remaining on the slave rolls until then. Her four children also became free at about that time.

Photo: Henry Trueheart

This piece of history, also shared by the guides during our recent visit to Monticello, got me thinking about the consistent nature of French civil servants. In not registering the Hemings siblings, Jefferson may have asked, for his own nefarious reasons, the same questions we transplants confront today: How strictly will the rules be enforced? What are the chances of getting caught if one doesn’t follow the requirements? How much power is in the hands of bureaucrats charged with enforcing the rules?

I can understand the reason for the COVID travel-test requirement. It’s not just that the U.S. has done a disastrous job managing the pandemic. France has experienced a big resurgence in cases in the past few weeks, so officials are understandably eager to prevent more spread from abroad. With the government determined to avoid imposing another nationwide lockdown, the increase has given rise to a plethora of bureaucratic rules. Among them: A map of where masks must be worn outside and within Paris that boggles the imagination.

Source: City of Paris

Friends and Facebook commenters who have preceded me back to Paris report mixed enforcement of the testing requirement. A family flying from Boston to Paris via Dublin wasn’t asked for results at all (Le Canard Enchainé reported that entrants from a third country are rarely challenged). Another pair of travelers, flying directly, had to show their test documents four times. This after one of them was rejected at the ticket desk because the results hadn’t yet arrived. A desperate call to the clinic fixed that.

Making matters more complicated, the person who will make the decision is NOT a French bureaucrat but an airline desk agent at a U.S. airport. All the techniques we transplants have cultivated over many years (stay polite, stand your ground, appeal to their sympathy, thrust 30 pages of documentation of any kind over the counter) may have less sway.

Air France says if I don’t have results in time for my flight, they can rebook me to the next day. After that, they’ll put me on the plane and I can get tested on arrival. Will things work out that way? No one, including Jefferson, can give me an answer for that.