Reprinted with permission from The Washington Post. See below for a response from the grown-up Henry.

August 28, 1999

PARIS — From what I understand, American parents yell and cheer so loudly at their children’s soccer games that many leagues now have to police their rowdy behavior. That’s never been a problem in France, where the loudest noise from the sidelines is often the sound of cigarette lighters snapping on.

As fall approaches, we are readying ourselves for another season of watching French soccer moms and dads do what they do best: stand around, look at their watches and leave for coffee.

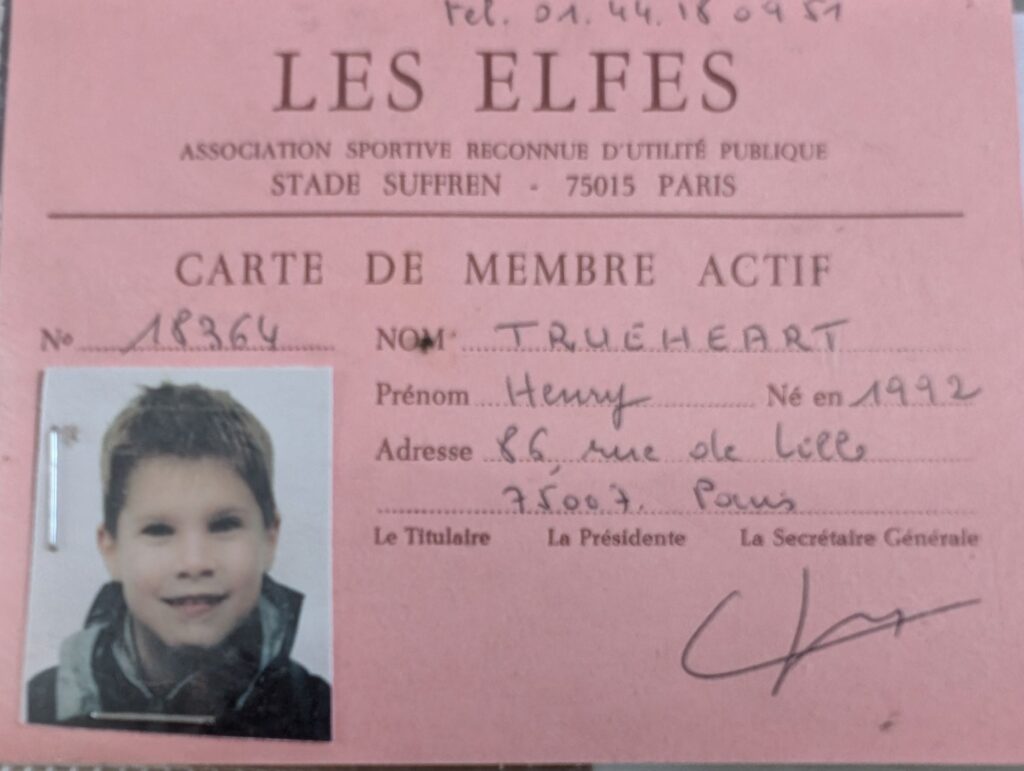

That’s if they show up. Last fall, I volunteered to drive to the first away game for my son Henry’s team. Henry was only 6, so I wanted to be there for his debut. My American friends tell me parental game attendance on their side of the Atlantic runs around 100 percent.

I got a clue that things operated a little differently here when the coach responded: “Thank goodness you can do it. If there aren’t enough cars, we can’t go.”

On the appointed Saturday afternoon, I arrived at the gathering place and immediately was entrusted with a carful of first-graders. Some of the parents didn’t even ask my name. “This is Pierre; this is Paul. Bye, boys,” said one dad as he turned over his two sons. I managed to get his cell phone number before he departed. I was glad I had that number; he was nowhere to be seen when we returned four hours later.

(Other cultural differences: When I told the kids in the car to put their seat belts on, two of them didn’t know how. And when we got to the game, I discovered I was the only parent who insisted on shin guards, to Henry’s humiliation.)

As play began, the parents–about one-third of the children appeared to have a relative present–straggled around the sidelines, muttering to each other. I thought one father was going to wax enthusiastic after he called out a soft “Bravo, Jean-Paul!” when his son made a good kick. Next time I looked, he was heading away from the field toward a nearby cafe, where a number of like-minded adults were holing up until the afternoon ordeal was over.

This blase attitude seems fairly widespread. Other parents tell me games involving older children also are conducted in near-silence. Games rarely start on time, and the parents who are there talk more on their cell phones than they do to their children or the coaches. Paris teams sometimes have to forfeit games in the suburbs because there are not enough drivers or because no one has a map and the whole convoy gets lost and goes home.

In Paris, the physical facilities devoted to children’s soccer are often not very impressive, either. Henry and his teammates play on asphalt, on a poorly lit basketball court at the French equivalent of the YMCA. Other fields I have seen are made of cinders or artificial turf. So unaccustomed are my children to real soccer fields with real turf that when they saw one during a visit to the United States this summer, Henry’s first question was: “Can I walk on the grass?”

French soccer parents don’t call the coach and complain about his decisions, either. They can’t; they usually don’t know his name. Henry’s team last year was coached by four different young men who seemed to come and go at random at the center where he played every Wednesday afternoon. They seemed amiable enough and knew who Henry was, but warm and fuzzy they weren’t.

It’s not that the French don’t like soccer, or don’t care about it, or don’t play it well. France, as no one here needs to be reminded, won last year’s World Cup. The final, against Brazil and played in Paris, gave rise to a rare outburst of national pride–in fact, it was one of the few times the French were truly demonstrative over anything but protest marches. The United States finished last out of the 32 qualifying teams. (The French, incidentally, were little impressed by the U.S. victory in the women’s World Cup this year. The newspaper Le Figaro devoted two pages the next day to the one-year anniversary of France’s masculine triumph and a three-sentence brief to the U.S. women’s success.)

Every French village seems to have its own soccer field. One million young people–96 percent of them male–play organized soccer in France. Even if only one-third of the parents attend games, that’s still a lot of people standing on the sidelines.

Christian Bromberger, an ethnologist at the University of Aix en Provence who studies soccer, pointed out that the behavior I witnessed is probably more typical of Paris than of the rest of France. Bromberger said he has seen French parents ream out the coach, and go at each other with umbrellas. At higher skill levels, parents also tend to be more belligerent on the sidelines. But he agreed that the atmosphere at youth games here is considerably calmer than in the United States. Perhaps, he said, that is because soccer here is more regulated. Every player from age 6 to 60 plays under the auspices of the national French soccer federation. Every coach, even of the youngest children, must undergo at least nine weeks of full-time training.

So when parents turn their children over to a team, they presumably have less reason to question the coach’s decisions–or at least less hope that things can be changed by objecting. “There is no self-management. Everything is regulation by institution,” Bromberger said. “If the coach doesn’t play the child, the parent can protest, but there is a structure against him.”

France is also a country where people don’t get all that excited about sports. Pro soccer games here are not subject to hooliganism, as they are in Britain, the Netherlands and Germany; the cheers from the stands are muted and sporadic. In this centralized country, people don’t feel pressure to conform in sports as they must in educational achievement or stylish dress. Perhaps half of Henry’s school friends play on a soccer team. “In America, government is democratic and sports are autocratic. In France, it’s the other way around,” quipped an American friend.

For better or worse, parents generally inject themselves less into their children’s lives here. Many schools, even elementary schools, don’t allow parents in the classroom. (On the first day of school in our first year in France, we had to leave our children in the front courtyard with teachers we had never met and whose names we didn’t know.) Parents cheerfully send kids as young as 8 or 9 away on ski vacations or to summer camp with what seems to us little concern or even interest in how well they will be supervised.

Certainly, the lack of adult enthusiasm doesn’t seem to discourage the children. One thing we notice here: kids playing soccer everywhere, all the time. In the parks, in the courtyards, on the street and, at least in Henry’s case, in the front hall of the apartment. When Henry goes to the nearby park, as often as not other boys are already playing there. Goals are backpacks or jackets laid in the dirt, lines are either drawn in the sand or nonexistent. Just last week I drove by a soccer field in the suburbs and a boy was out there, alone, practicing shots on goal.

We see parents playing soccer with their kids, too. Henry’s teammate Adrien is often out in the park with his dad, practicing headers or corner kicks. But that same dad said hardly a word during the game last fall. Maybe he just knows the right time to encourage his son, and at what volume.

Henry responds:

It’s true, I do remember asking permission to step onto a grass field in the United States as a young lad because the concept felt so foreign, so tantalizing. Playing on concrete was where I first started working on my craft, it was what we had and we did not question it. If anything, scrambling around trying to construct passing sequences on cobblestones did wonders for my ball control and mental fortitude. In fact, the epicenter of football talent has produced world class players for decades (see Kylian Mbappe, Thierry Henry, Paul Pogba, Riyad Mahrez, N’Golo Kante et al) and I was there starting in 1998.

What my experience playing soccer in Paris may have lacked in traditional American “team spirit” (see “Go get ‘em Tyler!,” “Great kick, Mason!,” “Good effort, Melanie!”) made up for in admiration for the game. Almost every single boy in my elementary school class would turn up for our lunchtime games, and all were invited to play. We weren’t interested in having the best players or winning the most games – we were interested in having fun.

And fun happens within the chaos of chasing around a ball, of losing yourself within the group and forming a cohesive ensemble where everyone plays an integral role just by existing within it. Soccer, in the vast majority of cases, is the great equalizer. It does not see class or race or status. It is language, though it needs no common tongue to be played.

In the United States, soccer has sadly ensconced itself in the “pay-to-play” framework that is so utterly exclusionary. It is a glaring difference between the two countries of my upbringing and how they approach the sport at a youth level. Parents in the U.S. can habitually face costs in the thousands of dollars per year for their child to participate in youth soccer, and that’s still before they’ve reached middle school. So, yeah, I might be a little bit more on edge watching my son or daughter play soccer in the U.S. considering it’s costing me hundreds of times the price of an annual club fee in Europe.

Of course, this kind of system also excludes wide swaths of the American population that cannot afford anything near the exorbitant demands that youth soccer puts on parents. According to a 2018 study by the Sports and Industry Fitness Association in 2018, a staggering 70% of U.S. children within the pay-to-play system came from households earning above $50,000 a year. I would challenge anyone to name me more than two or three national team players in any other country who grew up in such households.

The French parents may not have been following every move their child made on the field, and maybe they could have begrudgingly showed their faces to a few more games. But, as a child, do you really want to look over and see your Mom or Dad fuming on the sideline? (Fuming as in hotheadedness, not Marlboro Lights). Do you want them berating your coach because you only played twenty minutes this time?

Children want to play, they want to have fun, they want to run around and chase a ball with their friends — and then they want to go home and have a snack and watch a movie before bed and live in those moments, because it should be about the moments. I still play soccer regularly, in fact more consistently than I ever have.

Because it is exactly the release and the counterweight to all the heavier parts of life. It is the hour and a half where you stop thinking and you just are. It is the closest thing you will ever come to feeling like a child again, and that feeling should be unequivocally accessible to every single child regardless of what path brought them to the field that day. I love soccer for what it is athletically, but I really love for what it is on a human scale: a common language that knows no borders, no socio-economic disparities, and no shame.

Anne, what a beautifully written and informative piece. You’ve nicely combined your skill as a reporter with that of an artistic raconteur. Bravo.

One question from an American grandfather: Is it called soccer or football in France?

All the best,

Saul

Thanks so much! It is le football, or le foot for short, in France.

I loved reading this Anne – both your older article and Henry’s response. Both are revealing. Yours through observing, his through experiencing. Henry touched on a very basic and essential difference in the two cultures. I think your kids were very fortunate to have grown up in France.

Thanks so much, Pat. I think so too, and so do they!

Henry is right. Playing a team sport as an adult is close to being a kid again. I don’t know how/ why American parents are so competitive. Perhaps because they have never played themselves, or — more likely— it is the idea that their child might get a sports scholarship. The sad thing is that many times all that yelling turns a child away from sports.

Thanks Katie! It’s sadly true.

Anne, loved reading this!

As a former soccer mom, I find it fascinating! Your observations are so well described, as are Henry’s.

And now I’m a baseball grandparent, love going to those games too.

We are loud, to be sure.

But also well behaved, or I like to think so anyway

Thanks Babe! I’m sure you are always well-behaved. And for all I know, American parents in general are quieter at their kids’ sports games. And maybe French parents are noisier….

Both you and Henry are to be congratulated on capturing a fundamental difference between France and the US in the sports arena.

Thanks so much, I’ll pass that on!