My dad loved everything about Paris, but he especially enjoyed its residents’ daily struggle to get from one place to another.

With his little camera – what kind? So many things I wish I’d asked him – and its telephoto function, he’d focus on cyclists, or motorcyclists, or pedestrians. He was fascinated by their chaotic confrontations with cars, buses and other terrifying competitors for road space. And he loved how Parisians managed all that with little protective gear or sign of concern.

Photo: H.R. Swardson

He and my mother visited often after Charlie and I moved here with the children in 1996. My parents were the easiest guests imaginable. They’d play with their grandkids on Wednesday afternoons, the school half-day. And while we were working and the kids were at school, they would walk all day. From the Arc to Triomphe all the way to Invalides, for instance. Or Musée d’Orsay to Sacré Coeur.

Dad meticulously recorded every walk. And, later, compiled them all onto one map (Enhanced by me).

Photo: Christine Swardson Olver

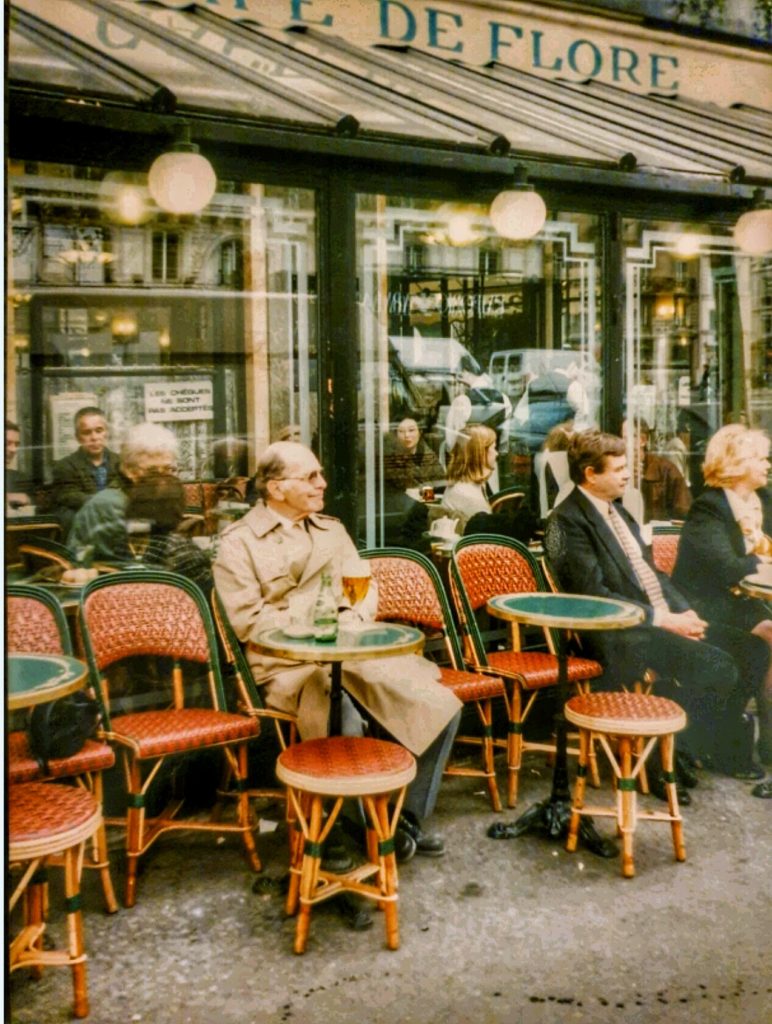

Along the way, he would take photos of Parisians going about their everyday lives and being very…Parisian.

Photo: H.R.Swardson

He adored mysteries: how young women in skirts could ride bicycles, for instance.

Photo: H.R. Swardson

And what IS in this guy’s hand? Dad called this one “the least explainable photo in my collection.”

Photo: H.R. Swardson

But his favorite subject always was situations that showed how in the midst of life we are in death.

An English professor for 47 years, Dad admired the French almost universally, except for their philosophers. Albert Camus was illogical and Jacques Derrida, the famed Deconstructionist who said a text was whatever the reader wished it to be, was contradictory. My father wrote numerous academic papers (three of them published after he turned 92) challenging the not-just-French notion that philosophy, and works of literature, don’t have to follow their own logic.

Come to think of it, maybe what he admired about Paris traffic was how people brought order out of chaos.

Still, Dad turned to Jean-Paul Sartre, an existentialist whose work I suspect he saw as mushy, in a last-ditch attempt to learn French. After 30 years of trying, he still hadn’t gotten much of it down. My theory is that he was so articulate in English that there wasn’t room in his brain for another language. He decided that he was going to learn via Sartre’s “Huis Clos,” No Exit. He practically memorized the entire play.

Then he attended a cocktail party given by the French department at Ohio University, where he taught. A French attendee rolled up his sleeves. Dad responded to this chance to make conversation by uttering a line from the play: “J’ai horreur des hommes en bras de chemise” – I can’t stand men in shirtsleeves. The party guest was not amused.

At least my father didn’t say the play’s most famous line: “L’enfer, c’est les autres” – Hell is other people. The French-learning effort petered out soon after that, though Dad still enjoyed Sartre’s hangout on his Paris visits.

Photo: Mary Anne Swardson

He died last month of heart failure, at 95, with my mother and his youngest daughter at his bedside. He said over and over that he was ready to go, and that he had had a good life. My kids – adults now — were home in Paris for Christmas and were able, with me, to say goodbye to their Pipaw on video.

A few days later, when we four were spending a week in the Loire Valley, my son Henry suggested we read “Huis Clos” aloud as an homage to Dad. We did: the bilingual offspring, the husband with the perfect accent, and me.

When we got to the line about bras de chemise, we all said it together.

Photo editing: James Schwartz