Imagine: The head of a governmental jurisdiction orders his underlings to scan the electoral database and remove anyone who might not be a citizen, without clear standards of proof. More than 1,000 people are turfed off the rolls. The national government files suit to reverse the order. Two lower courts agree but the move is upheld by the highest court in the land.

This could never ever ever happen in France, or practically any true democracy. But it happened in America, in Virginia, the state where I spend a lot of time these days.

Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin ordered the purge during what by federal law is supposed to be a 90-day quiet period ahead of Election Day. His purported reason was to keep noncitizens from voting. In the last 20 years no one in Virginia has been charged with casting a ballot illegally.

About 1,600 people, many of them citizens, were removed from the rolls. Many weren’t even aware of it until told by journalists.

In France, it would be as if the mayor of Nice told his deputies to scan the municipal electoral rolls (France doesn’t have states and its administrative region have little power) and strike out anyone who might not be a citizen.

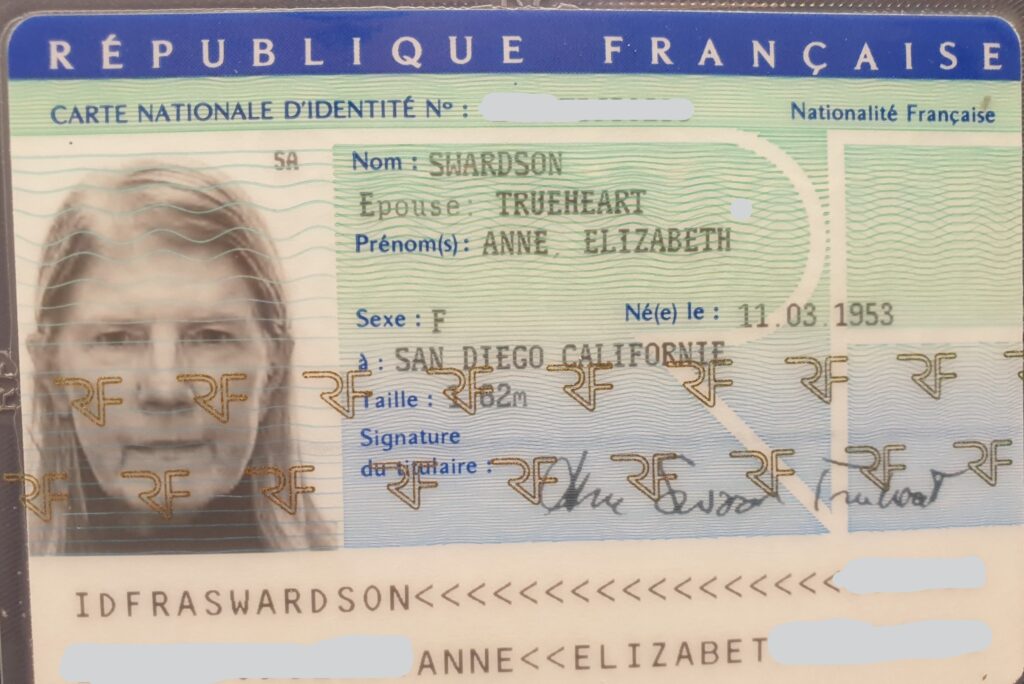

Except the electoral database is entirely national. Also, there’s no such thing as “might not be a citizen.” Every citizen (including me, naturalized in 2009) has a national ID card, which you show when you vote. I wrote about that here. You either are a citizen or you aren’t.

The idea of a national ID is unpopular in the U.S. – ironically, especially among Republicans who insist on voter ID. Or not so ironic, since the contradiction is really just another way of keeping low-income people from voting.

The methods of proving your identity, when registering and when voting, vary by state, as this chart shows. In Arkansas, you can use your concealed-firearms license. Not a lot of that happening in France.

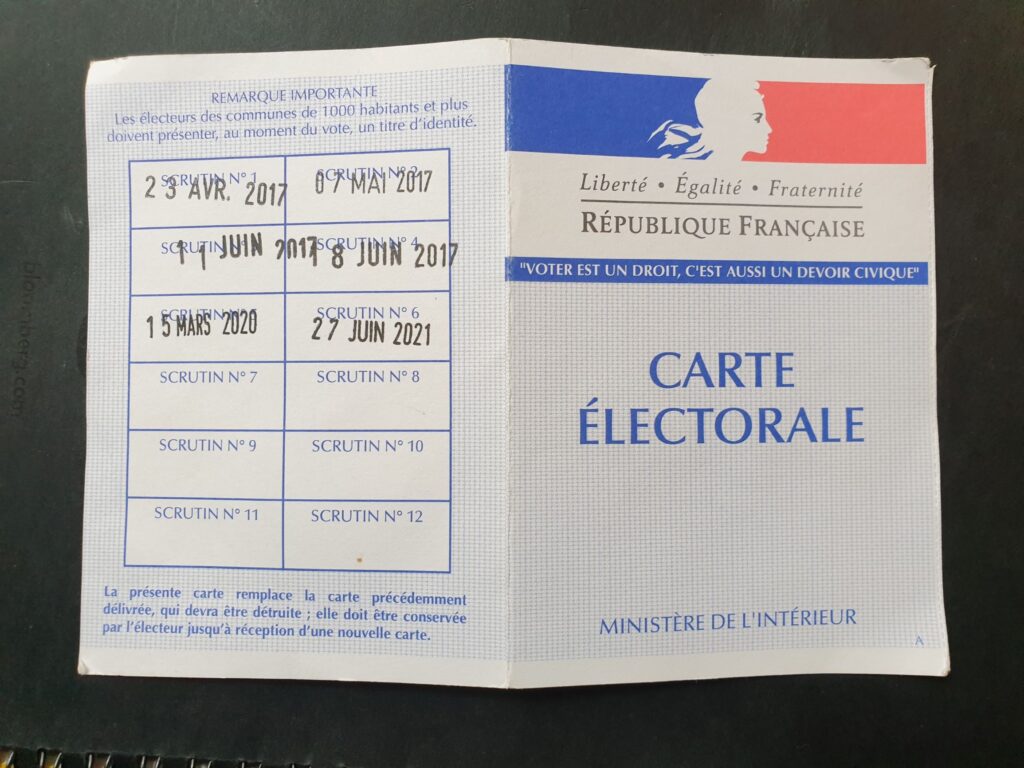

In France, registering to vote happens automatically when you turn 18 or when you become a naturalized citizen. Or you can register online, providing a form of ID and proof of where you live, like a utility bill. For each election you get a separate voting card by mail beforehand. It’s not required but you can get it stamped for each election you’ve voted in. Volunteers and paid employees man the polling places and, needless to say, are never threatened with violence.

France does have some electoral peculiarities. There is no early, mail or absentee voting, for instance. If you can’t be at your polling place day-of, the only possibility is to vote, as I did last summer, by proxy.

Nor does the centralized French system always produce the best of democracy. For example, politicians can hold more than one office at a time: national legislator and city councilor, for instance. Or mayor and member of the regional council. The practice has been reformed in recent years but it still blocks new talent from climbing the electoral ranks.

But there’s a difference between an electoral system and politicians attempting to game that system. You don’t see any of the latter in France.

The Virginia confusion over citizenship arose mostly because people failed to check the “citizen” box when they applied for driver’s licenses. (Odd as it may seem to French people, our chief way to prove identity is with a card that says we know how to drive.) Some of the expunged became citizens after getting their driver’s licenses and before they registered, or just overlooked checking the box.

Ryan Snow, a lawyer for one of the groups challenging the removals, said he had talked to a naturalized citizen who had voted for 30 years.

“It’s very important to him,” he told the Washington Post. He “never had an issue with voter registration, and all of the sudden, he’s removed.”

As far as I can tell, the Virginia affair wasn’t reported in France. Perhaps that is because on the list of crazy these days it barely registers. And Virginia law allows those affected to re-register up to Election Day if they can prove citizenship.

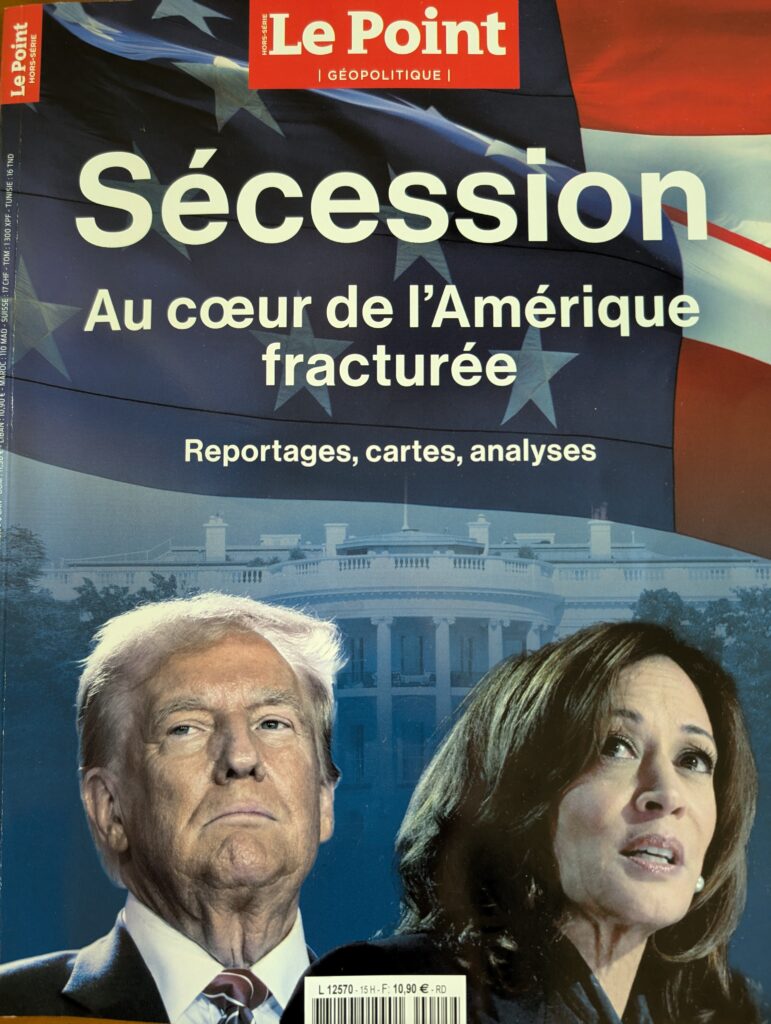

The U.S. presidential election is being covered widely in France, especially the rallies of Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. In this post on cable news channel BFM, the reporter describes the record gender gap between the two candidates, the various stars who have lined up for Harris and the importance of the swing states (les états clés).

Le Monde, the most prestigious and intellectual newspaper, devoted 2,200 words to explaining the U.S. election process, including “le collège électoral.” The system is “extremely decentralized, organized by states, counties or municipalities: None manage elections in exactly the same way, each has its own electoral code, and there are important variations.” To put it mildly.

It took Liberation newspaper only 800 words to do the same but the authors did take the time to call the process “complex and sometimes unfair,” which it is.

In this special issue of Le Point magazine, whose subtitle is “In the Heart of Broken America,” articles examine our polarization over immigration and abortion, the paradoxes of a booming economy that voters don’t believe in, student protests over Gaza, fundamentalist Christian support of Trump and our vacillating foreign policy. Sometimes others see us more clearly than we see ourselves.

Good summation. The truth hurts.

Thank you! About the post, not about the truth hurting.

What a wonderful post. The French system is not perfect but I definitely like some aspects it. I love the registration at 18 and the voting booklet. It is like a vaccination record. Why is this country so polarized that we want to deny people the right to vote? It should be like healthcare which I believe is a right of all citizens who live in they country. One of our NY friends who lives in Normandy now (she is French) had her ballot denied for this election for an unknown reason. She had voted in the US for at least 50 years. Until we come together in the US, these problems will persist.

Thanks for your thoughts. How terrible about your friend!

Thank you Anne. The French system seems so calm, so reasonable and sane. Something to aspire to, but alas, not in this election.

Congratulations on this bracing denunciation of inequality in our electoral system (if that’s the word).

Merci!