France’s presidential election has me reflecting on the French language. Over the past few months of campaigning, I’ve heard words I didn’t know but could learn, words I didn’t know that were hard to translate and words that even French people didn’t understand.

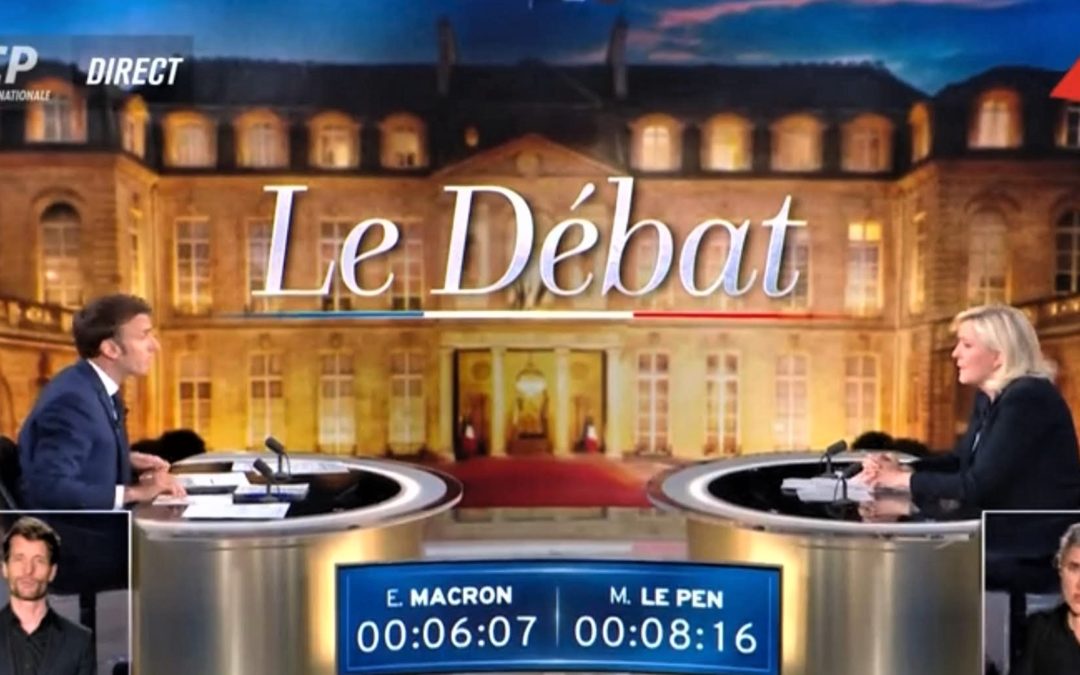

When it comes to talking, centrist President Emmanuel Macron is a champ. In his April 20 debate against the far-right Marine Le Pen, he set Google abuzz with words like “ripoliner,” which means to paint with gloss and was a reference to Le Pen’s attempt to soften her image.

Nombre de recherches du mot « ripoliner » sur Google #DebatMacronLepen pic.twitter.com/Oly0NUQ86T

— 🗳 → 🇫🇷🌎🫱🏻🫲🏾 (@GuillaumeRozier) April 20, 2022

Other fancy words, as noted by Chris O’Brien in French Crossroads and by The Local, included “rabougrissement” (to stunt growth, used mostly by gardeners), and “outrecuidance” (to be overconfident). It’s hard to imagine the elite Macron telling someone ELSE they were overconfident.

Le Pen, whose voters admire her plain style of speaking as well as her anti-immigrant views, had fewer rhetorical flourishes. But she did use one of my favorite hard-to-translate words: “precarité.”

It technically means “precariousness” and refers to the state of having a job from which you can be fired or laid off, which pretty much no one wants in France. She accused Macron of increasing “precarité” during his five years in office, without admitting that unemployment dropped during the period to the lowest since 2008, in part because of his economic reforms.

The debate was seen as a crucial turning point in what had developed into a close race, after the first round of voting two weeks ago vaulted the two into the second round. Le Pen, who lost to Macron in 2017, wants to reduce France’s role in the European Union, forbid foreigners and non-native-born citizens from having equal access to public-service jobs and hold a referendum on “stopping” immigration. And that’s the detoxified version of her program, compared with 2017.

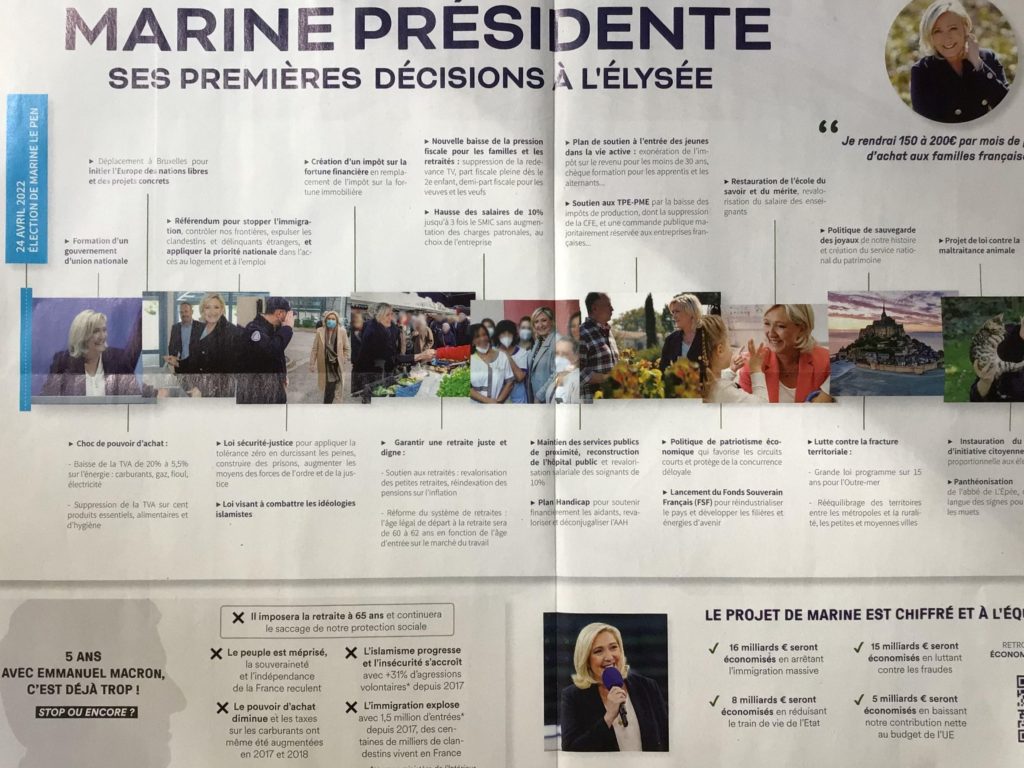

Here are her positions, in the handy brochure that showed up in the mail the other day.

Macron has to struggle with the burden of being an incumbent and thus having a record. The French word for incumbent, incidentally, is “sortant,” which means outgoing or exiting. Technically that’s true for Macron since his term is expiring but it sounds odd since he’s running again.

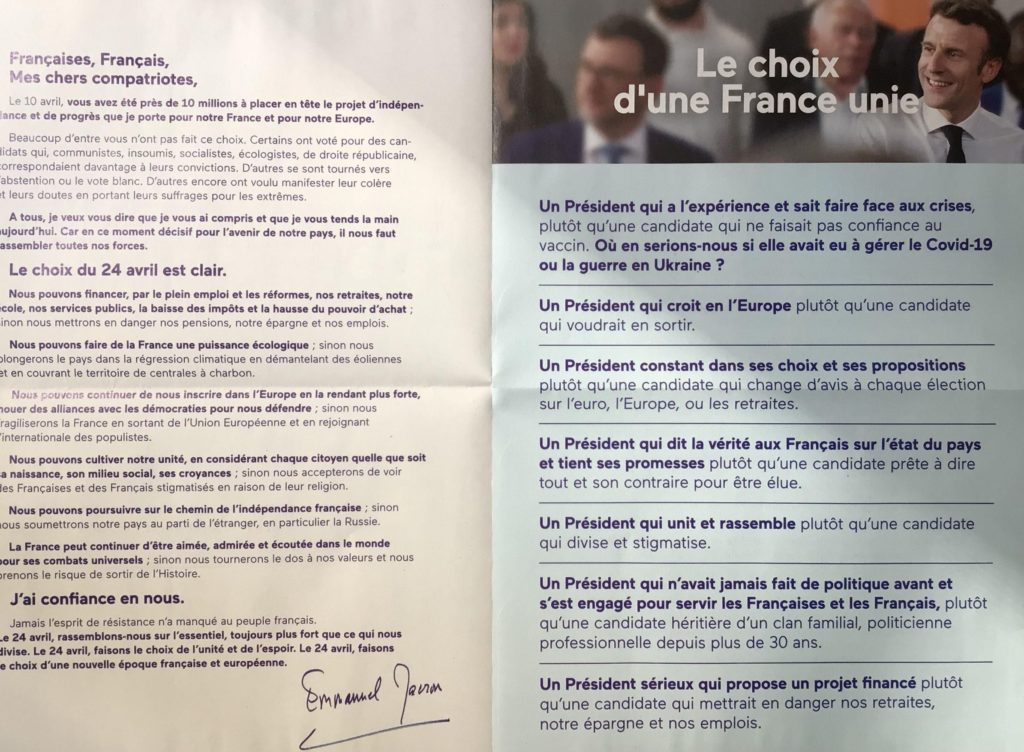

The result was a campaign that emphasized his experience, such as his attempts to negotiate a settlement in Ukraine, while promising to do better when it comes to issues that touch voters directly, like rising gasoline prices. He implied flexibility on his plan to raise the full retirement age to—quelle horreur—65.

The general consensus after the debate was that Macron had kept his ego more or less under control and Le Pen had shown a greater mastery of the material than she had in 2017, when she fumbled through stacks of pages and got many facts wrong. She got facts wrong this time around, but it usually was on purpose. Like when she used an outdated figure to criticize Macron for the loss of manufacturing jobs in France, using a number that was three times larger than the latest data.

Toward the end of the debate, the two started talking about a term that is truly untranslatable: “laïcité.” It technically means secularism. But to really understand its current usage, especially by the political right, you have to know that a 1905 law made religion and state entirely separate. At the time, the intent was to keep the Catholic Church out of government affairs. But now, rightist politicians have used laïcité to crack down on what they see as radical Islam and what many of France’s 6 million or so Muslims see as normal habits of worship and dress.

Le Pen wants to ban the wearing of Muslim headscarves in public, which Macron said went against the “tradition of the French spirit and of the Republic,” without adding that his government passed a law against “séparatisme” —another tough-to-translate word—last fall that made it easier for the government to close mosques seen as radical. In France, you are not supposed to want to follow the customs of your ethnic group, original country or race. You are supposed to just be French, like all those other white people.

The debate gave Macron a boost and it would be a big surprise if he didn’t win Sunday. But, as John Lichfield points out, the fragmentation of French politics means he will have a hard time getting much done, especially since his own party is really just a personal vehicle.

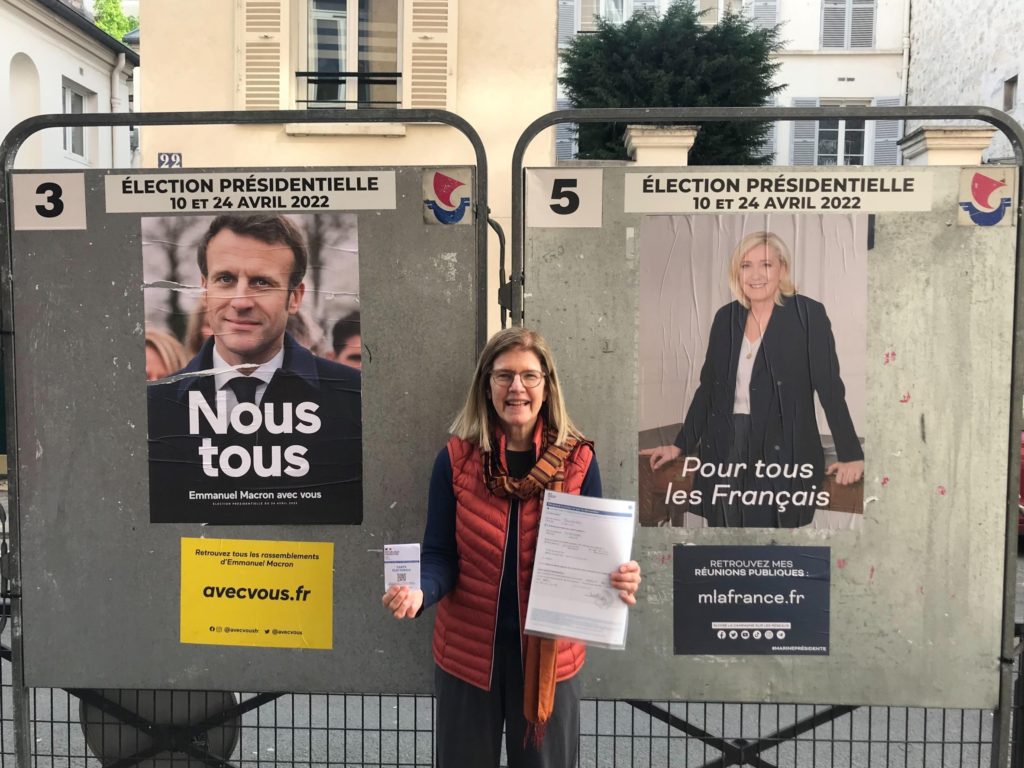

One thing is certain: The election will be fair and well-run. Charlie and I were reminded of that the other day when we stopped by the police station—on a holiday Monday!—to have me certified to vote his proxy, since he will be away.

And now, the “temps de parole,” the time for speaking, is over. By law candidates can’t make speeches, pollsters can’t release polls, journalists can’t write opinion pieces and “propaganda” can’t even be posted on social media during election weekend.

Learning new words is good and not hearing words for a while is also good.

Succinct, well-put and educational. Felicitation, Anne!

Merci, Andy!

Thank you, Anne, for the update on the election. Do hope M. Macron wins on Sunday !

Thanks so much, Patty!

Interesting. For new words, Raymond Barre (all those years ago) was the best. But my question is about arrogance. It seems to me that Macron’s much discussed arrogance is youthful more than disdainful. But I began wondering whether he appears to the French the way that the French can maybe sometimes perhaps appear to Anglo-Saxons. Soit, arrogant.

Yeah, my memory is that French presidents were always arrogant. I mean, De Gaulle? Not so much Pompidou but Giscard and Mitterrand personified arrogance. So in that sense Macron is just following tradition. Though he IS arrogant, like, he’s always been the smartest guy in the room and knows it.

Very well summarized. This an election between the “cœur” and the “raison”. Marine’s voters love her because she’s convinced them that she’s one of them (a minette brought up in private schools in St. Cloud). The Heart has reasons that Reason doesn’t know.

Eh comment!

Great to have your insights. Le Pen would be a disaster for Ukraine and the Western alliance. Hoping for a Macron win.

Merci, Richard!

Great piece, Anne!

But, I don’t quite get why people think that LePen is so much stronger now than in 2017. In the first round this year she got about the same % of votes (23.1%) as she got in the first round in 2017 (21.3%) +1.8%, Macron got considerably more in 2022 (27.9%) than in 2017 (24%), +3.9%. Of course, all the “normal” parties have lost their following, and the extremes, left and right. My take is that people express protest votes in the first round, and then make an intelligent choice in the second round. Perhaps the “cœur” vs. “raison” element that David notes above.

Yes, it’s true, Walter, that voters tend to vote their hearts in the first round and their heads in the second round. But there are a few particularities this time: In the first round, Le Pen was also running against the even-farther-right Eric Zemmour, who got 7%. So some of those votes would have gone to her and presumably will in the second round. Also, Politico’s poll of polls showed the two separated by only five points in early April, which is almost within the margin of error. That never happened in 2017. The gap has widened since then, though, and it’s true that Macron is more popular, at 43%, than any of his recent predecessors. Of course, none of them was reelected 🙂

Great read as always!

Thanks so much!

This was fascinating and very helpful for an American. Thanks for taking the time to provide a thoughtful analysis.

Many thanks, I’m glad you liked it!